Book reviewed by Charles Sherlock, May 2025

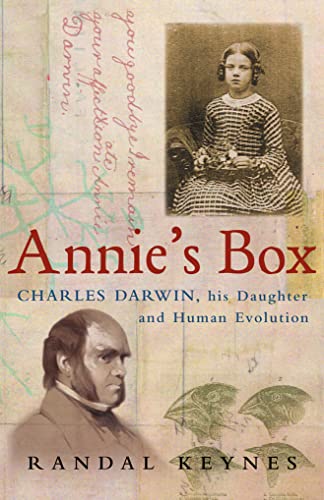

Annie’s Box: Charles Darwin, His Daughter and Human Evolution

by Randal Keynes

London: HarperCollins Fourth Estate, 2001; xvi + 334 pages

ISBN 9781841150604, first edition, hardcover

AU$60

Randal Keynes is the great-great-grandson of Charles and Emma Darwin. Annie, their first daughter, after a joyful life died aged just ten. Looking through “a case of odds and ends one day,” Keynes found her box of treasured things, including a lock of her hair, that her mother had kept. With the box was a note, in Charles’ “untidy writing,” detailing Annie’s last illness, and a “memorial” of her that he penned. In time they had been forgotten.

Keynes was intrigued and began to piece together the story—and its lasting impact on Darwin’s work. The result is a work of social history, focusing on the people involved. This beautiful book follows the marriage of Emma and Charles, and its impact on his developing ideas about human evolution. It is well-organised, readable, and interesting. Its high level of detail never gets in the way.

Alongside the main interest, Darwin’s ideas, Keyes paints a picture of life in well-to-do English families who had benefitted from the Industrial Revolution. Helpful resources include a list of the Darwin and Wedgewood families, together with close colleagues, two sections of photographs, many illustrations, detailed notes, and a full Index.

The flyleaf (p. vii) cites a letter of 1863 from Charles to his long-time friend, botanist Joseph Hooker: “Much love, much trial ….” These words speak eloquently of both Charles’ family life and of his emerging insights into nature. The suffering involved in his concept of evolution increasingly worried him: it would see him cease regular churchgoing to become an agnostic (his word), though he could not see the world arising from chance.

Keynes’ thesis is that memories of Annie’s happy life and untimely death shaped Emma’s and Charles’ worldviews for the rest of their lives. I am not in a position to assess this claim, but Keynes backs it with evidence and uses it to show the importance of feeling in Charles’ scientific work. His book is significant for Christian understanding of and responses to Darwin’s ideas in several ways.

First, after the voyage of The Beagle as a young man (21 to 26 years), Charles’ whole life was spent working in and around the large family household. This environment played a key part in his instinctive habit of constantly assessing his ideas. He was a warm-hearted father, and delighted in his children, but could not help recording their stages of growth and awareness of others. In his opening comments Keynes thus writes, “There is one idea at the heart of my account. Charles’ life and his science were all of a piece” (p. 1).

Secondly, Darwin’s work showed our human kinship with animals. More than the concept of evolution—in his day questioned mostly by scientists—it was this idea that saw him pilloried in the popular press and in many pulpits. Yet his greatest concern about his discoveries was the enormous suffering involved in the struggle for life to emerge. It is this, Keynes argues, that saw Darwin gradually leave Christian faith behind.

Christian engagement with evolutionary ideas has gone on for 150 years or more. Darwin’s life has been scrutinised by several authors, and his scientific insights (and their social consequences) have been tested and refined. Christian responses have been many and varied—and still keep coming. Why recommend yet another book on the topic?

First, setting Darwin’s work in the context of his household uncovers the close association between nature, human feeling, and the emergence of social networks (as among other animals). This is part and parcel of Keynes’ empathetic analysis of Darwin’s shifts in spiritual understanding. Such an analysis questions too-easy criticism of his work, and calls readers to the often-costly journey of integrating faith and life-experience.

Secondly, this book makes Christian readers aware of the significant changes in Christian theology that have come about in the wake of Darwin’s work, but were hotly contested in his day. An obvious example is the widespread abandonment of Archbishop Ussher’s dating of creation in 4004BC, as theologians have come to terms with geology. In the past century, Darwin’s struggle over suffering has been amplified by its horrors, leading theologians to reassess the traditional notion of divine impassibility, and accept that suffering lies at God’s heart—an emphasis now seen in some hymns. Most recently, environmental awareness has led theologians to stress human “sixth-day solidarity” with other animals, rather than contrasting us with “brute beasts.”

Keynes notes that the Darwin and Wedgewood families, though attending their Church of England parish churches, were Unitarians (which Keynes documents). But seeing the God of Israel as capricious and violent, and rejecting the doctrine of the Trinity, leads to God being experienced as distant. And being uncomfortable with the biblical emphasis on redemptive suffering leads to downplaying the passion of Christ. Did the memories kept by Emma and Charles of Annie’s death and life in some way fill this gap for them?

It is well known that Charles and Emma had divergent theological views: Keynes points to their conversations about this as part of their considering marriage. Emma put great store in the hope of life after death, which Charles increasingly questioned, though neither seems to have related it to the resurrection of Christ. If they had lived out of a more Christ-centred worldview, what difference might that have made to both their lives, and science?

I warmly commend this book, especially to Christians involved in science and theology. As well as shedding light on the interactive and human aspects of both, it can be read as an invitation for followers of the Lord Jesus to integrate faith and life with integrity.