Abstract: The biblical account of origins includes the creation itself (Genesis 1–3) and the origins of civilisation, religion, and languages (Genesis 4–11). Ever since these accounts were first written down there have been questions about their meaning, and about how literally they should be taken. To grasp their meaning we need to understand their origins, but for most scholars the traditional view that they were written down by Moses is not consistent with the evidence from the texts. This causes difficulties of understanding, so that a reconsideration of the origins of the accounts is a necessary precursor to speculations about their meaning, especially in relation to the faith–science dialogue on cosmic origins. A viable explanation for the origins of the biblical creation accounts should explain the evidence for multiple documentary sources, as well as the historical origins of these sources. Such an explanation was outlined by William F. Albright, who attributed the creation accounts of Genesis to distinct Priestly and Yahwist traditions, while also affirming that much of this material was brought from Mesopotamia during the time of the patriarchs. This raises the question of how multiple accounts of origins could be preserved in the family history of one man (Abraham). However, this is possible if the Mesopotamian origins accounts included both oral and written sources. These different media would have allowed the preservation of conflicting accounts of origins that eventually fed into the tribal histories of Israel, now recognised as the Priestly and Yahwist traditions. This represents a testable model for the origins of the biblical accounts, allowing the possibility of a new understanding of biblical origins in Genesis, both as texts and as histories.

Keywords: Abraham; Creation account; Documentary Hypothesis; Priestly; Yahwist

For centuries, thinkers of all persuasions have been wrestling with the meaning of the creation stories of Genesis and the question of how they relate to nature and science. The debate has often been strongly polarised. For example, one extreme is represented by recent authors who claim that Genesis is basically a scientific textbook.[1] They give an interpretation of Genesis as if it were directly dictated by God, which overlooks the complexity of the biblical text and its long history of transmission.

Alternatively, if we could make a reasoned argument about the origins of the text, we could make a better case for grasping its meaning. However, when we follow this approach, we quickly run into another extreme of interpretation, which says that the origins of these texts cannot be known. This is based on the view that present explanations have failed, and that there is nothing new to be said: “After two and a half centuries of modern research, all conceivable arguments have been brought to the table.”[2]

This sounds much like the opinion of nineteenth-century physicists that there was nothing new to find in science, a belief that was held shortly before the discovery of radioactivity, relativity, and quantum mechanics. However, what this belief really showed was that thinking by a small self-selecting group of scientists had become sterile. I suggest that a similar type of tunnel vision has occurred in the present-day biblical studies community.

This is the basis for bringing new ways of thinking, such as those used by scientists, to the field of biblical studies; and this can conveniently be initiated by an examination of the issue in a journal that is designed for the interaction of science and faith. Such an examination is important because the early chapters of Genesis underpin the Bible’s view of the relationships between God and humanity. For example, those engaging in the creation–evolution dialogue and those ministering in the area of marital relations often begin their discourse by quoting from the story of Adam and Eve. Therefore, an understanding of the historical origins of these texts is a foundational issue for Christianity that is highly relevant to members of ISCAST (Institute for the Study of Christianity in an Age of Science and Technology).

The Mosaic Tradition

Traditionally, the authorship of Genesis was unquestioningly attributed to Moses, since Genesis is the first of the “Five Books of Moses” (the Pentateuch). But even though Exodus says that Moses wrote down God’s “words” (the Law), there is no statement that Moses wrote Genesis, and certainly no claim that he wrote it down for the first time. Therefore, it is not surprising that increasingly critical questions were asked about the Mosaic authorship of Genesis when scholars reexamined traditional and received wisdom during the “Age of Enlightenment.

One of the first to ask questions about the Mosaic authorship of Genesis was Benedict Spinoza. He suggested that the use of anachronistic place names and phrases, such as “to this day” (Genesis 22:14; 26:33; 32:32), implied that the Pentateuch was written much later than Moses, probably after the Jewish exile in Babylon.[3] On the other hand, Jean Astruc attempted to reinstate Mosaic authorship of the Pentateuch by arguing that Moses himself had edited together two earlier written documents.[4] Astruc identified these documents based on their use of two different Hebrew names for God, usually romanised as Elohim and Yahweh.

Later scholars abandoned Astruc’s belief that the editing process was carried out by Moses, but adopted his idea that Genesis was composed from documentary sources that used different names for God. Hence, the Documentary Hypothesis was born. But if Genesis (and the Pentateuch as a whole) was composed by combining preexisting documents or sources, it is critical to have objective and consistent criteria to identify these sources.

Here, it should be remembered that the gospels of Matthew and Luke show clear evidence of having been derived by combining distinct source traditions.[5] For example, Matthew’s gospel contains almost all of Mark, in a somewhat condensed style, interleaved with another source that is common to Matthew and Luke (often called Q), and additional material (such as the story of the Magi) that is unique to Matthew. So the compilation of Genesis from distinct sources is not in itself problematical.[6]

The Documentary Hypothesis

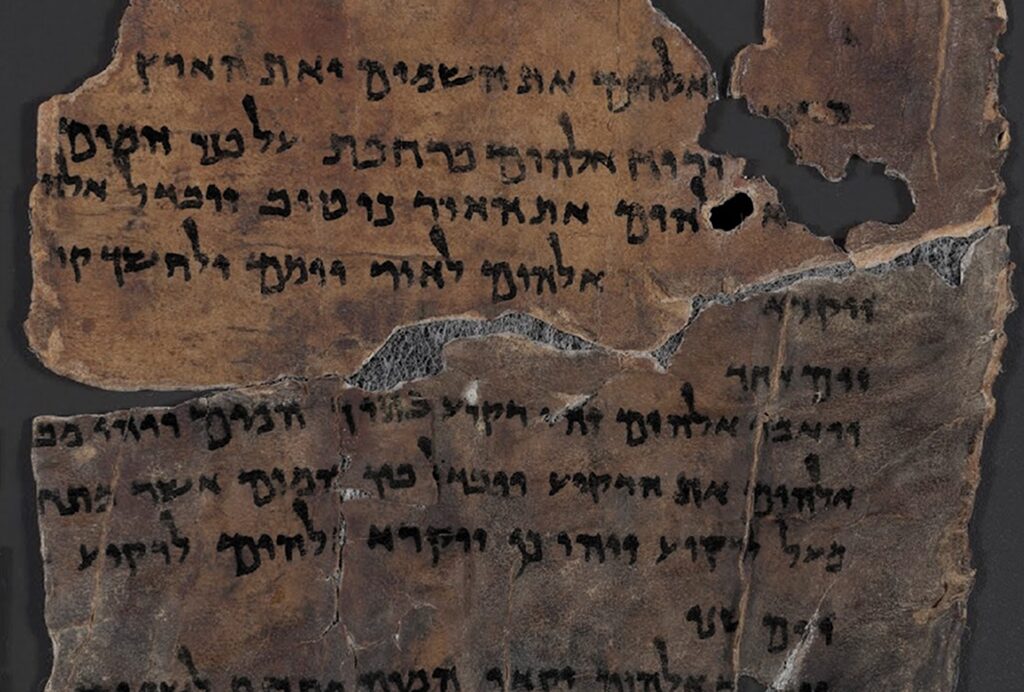

The principal result of 19th-century scholarship on the Documentary Hypothesis was to recognise four main sources to the Pentateuch; the Yahwist (J), Elohist (E), Deuteronomist (D), and Priestly (P) sources, whose acronym in German, JEDP, signified the most popular theory on the relative ages of the sources. In addition, one or more redactors presumably combined these sources into what we have in the Masoretic Text, the Septuagint, and the Dead Sea scrolls.[7]

Two of the principal sources in Genesis (J and E) can be described as epic sagas. They use different words for God (Yahweh and Elohim) but are stylistically similar. The P source also refers to God as Elohim (in Genesis) but has a very different style, displaying an interest in genealogies, covenant agreements, and lists, with a more rigidly organised content rather than a focus on dramatic story development. The D source does not contribute to Genesis, but claims to be the last speech of Moses, representing a summation of the Law intended to guide the Israelites in their conquest of the Promised Land.

Once identified, the ages and origins of these sources can be investigated in order to understand the origins and meaning of the text. However, scholars have always tended to mix up these two stages of thinking in their application of the Documentary Hypothesis, conflating straightforward source identification with the theological analysis and historical interpretation of source traditions.

For example, it was observed in the 19th century that in their preaching to the House of Israel, many of the biblical prophets seemed not to refer to large segments of the law, which implied that perhaps they did not have access to those parts. The Bible gives its own explanation for this observation in 2 Kings 22, which describes the finding of a “lost scroll of laws” in the temple. The claim that this scroll was found in the time of King Josiah immediately explains a previous lack of knowledge of part of the law (normally assumed to be Deuteronomy). But rather than taking this account at face value, Wilhelm de Wette developed a perverse alternative theory that this scroll of laws was a “pious fraud,” newly written in the time of Josiah and planted in the temple expressly to be “discovered” by the temple servants.[8]

This theory introduced the whole idea of the Pentateuch as an “invented history” of early Israel. This line of thinking was developed by Wilhelm Vatke,[9] who argued that Israelite religion developed from a primitive laissez faire style of worship in its early phase (by which the patriarchs could offer sacrificial worship anywhere they felt to be holy) to an increasingly regimented cult overseen by a temple hierarchy. According to this Development Hypothesis, the ceremonial law supposedly received from God by Moses did not actually arise until after the Babylonian Exile. However, the conclusion of this line of thinking, initially spelled out by Karl Graf[10] and fully synthesised by Julius Wellhausen,[11] was that the whole paraphernalia of the Tabernacle and Mosaic ceremonial law described in Exodus was an elaborate fiction.

This proposal represents a clear denial of the New Testament view of Old Testament religion, such as that summarised in the eleventh chapter of the Letter to the Hebrews. But Wellhausen’s rhetorical skills allowed him to hitch together the Documentary and Development Hypotheses, so that accepting the reality of source documents for the Pentateuch more or less meant treating them as fiction. The result was that most Evangelical Christians vehemently rejected the Documentary Hypothesis lest they also be accused by their churches and academic institutions of heresy. In contrast, most liberal scholars embraced the Documentary Hypothesis with enthusiasm, but as generation after generation of thinkers tweaked it, the basic principles of source identification underpinning the Documentary Hypothesis were gradually abandoned.

One of the notable recent steps in this process was the publication of a collection of papers in 2006 under the title A Farewell to the Yahwist.[12] The message was that one of the most well-established documentary sources, J, did not exist as a coherent tradition, but was simply an agglomeration of fragments. One of the marks of this way of thinking was to abandon the label “Yahwist” and simply refer to such material as “non-P,” meaning any text that was not stylistically identified as part of the Priestly source.

A more recent analysis of the J source in Genesis demonstrates the type of arguments used for its dismembering. For example, in identifying a lack of continuity between the non-P material in the primeval and patriarchal narratives, Jan Christian Gertz suggested that “the Patriarchal material seems to esteem the semi-nomadic lifestyles of the patriarchs and their families, which according to the primeval history must be regarded as unsettled and cursed.”[13] This assertion is evidently based on the idea that God’s cursing of Cain with wandering in the Land of Nod was a criticism of the nomadic lifestyle. But this seems to be far from the truth—the sacrifice of Abel the pastoralist was accepted by God, whereas Cain’s, the (settled) farmer, was rejected. Similarly, the story of Babel implies judgement against the city and approval of the nomadic lifestyle.

In response to this type of argument, a return to the basics of the Documentary Hypothesis has been advocated by a new generation of scholars, including Joel Baden and Jeffrey Stackert.[14] They argued that documentary sources should be distinguished on basic matters of narrative consistency or inconsistency in the description of past “events,” and on evidence for basic matters of belief, such as the revelation of the name of God, not based on value judgements about the theological message of different segments of the biblical text.[15] This view has been labelled the “neo-documentarian theory” by some, although to a large degree it involves a return to its roots.

To demonstrate that such a return is justified, we need to examine some specific texts that clearly suggest the existence of multiple sources for several Old Testament books, and which may also reveal relationships between these sources. We also need to assess the continuity of these traditions based on their fundamental characteristics as sources, rather than subjective judgements about their theological message. These assessments are the necessary first steps in understanding the origins of the creation accounts of Genesis.

Evidence from Conflicting “Eyewitness” Narratives

The strongest evidence for the Documentary Hypothesis (in the Pentateuch and in the following historical books) has always been the existence of multiple accounts of events with conflicting details. For example, the case for separate Priestly and epic saga sources can be seen clearly in the description of the birth of Benjamin (Genesis 35). The P source (Genesis 35:23–26) describes the birth of Benjamin in Paddan Aram, as part of a list of all the sons of Jacob organised according to their mothers (Leah, Rachel, and their two maidservants). In contrast, the E saga describes the birth of Benjamin between Bethel and Ephrath in Canaan, as part of a vivid account of the death of Rachel (Genesis 35:16–20). These two accounts are clearly contradictory, but because one is a genealogical catalogue and the other an eye-witness story the contradiction is not obvious. Editing either account for consistency with the other would have done violence to the narrative, so the redactor preserved the minor conflict between them, and most readers do not notice it.

A more obvious example of two conflicting versions of events comes from the life of King David, hundreds of years later (1 Samuel 16–17). Here, the events surrounding the killing of Goliath and David’s promotion to the royal court are described in two significantly contradictory accounts. Although these accounts are in 1 Samuel, one of the sources was identified by Richard Friedman as the same J tradition considered a principal source of the Pentateuch. In fact, Friedman claimed that this narrative account was a continuous saga that described the history of the nation of Israel from the origins of humanity to the reign of David, with addenda up to the Jewish exile in Babylon.[16]

In the book of Samuel, this J source describes the anointing of David (son of Jesse) to be king, consistent with the Judean tribal history prophesied by Jacob in Genesis 49 (also attributed to J). According to 1 Samuel 16, David was sent to the court of King Saul because of his ability to play the harp, after Saul began to be tormented by an evil spirit. The result of this encounter is described as follows (1 Samuel 16:21–22, NIV): “David came to Saul and entered his service. Saul liked him very much, and David became one of his armour-bearers. Then Saul sent word to Jesse saying, ‘Allow David to remain in my service, for I am pleased with him’.” After this, J goes on to describe how the Israelite and Philistine armies confronted each other at Socoh, and how the Israelites were terrified of the Philistine champion, Goliath. However, this account of David’s promotion to the royal court is followed by a second version with a significantly different record of events.

This second account gives a detailed description of David’s killing of Goliath (1 Samuel 17). But as David is going out to meet Goliath, Saul inquires of the commander of the army (17:55), “Abner, whose son is that young man?” to which Abner replies (17:57), “As surely as you live, O King, I don’t know.” Then, a little later, after the killing of Goliath, Abner introduces David to Saul while David is still holding Goliath’s head in his hand. Saul now asks David himself (17:58), “Whose son are you, young man?” Hence, these quotes clearly show that in this version of the story, Saul had never met David before.

Evidence for the identity of the second source comes earlier in the chapter, where the Ephrathite ancestry of David’s father is noted (1 Samuel 17:12). The Ephrathites are believed to be a clan that originated from the tribe of Ephraim, whose territory was in the north of Israel. These Ephraimites apparently migrated to the Bethlehem area south of Jerusalem, and are believed to have married into the tribe of Judah through the female line (in the person of Ephrath); hence their name, Ephrathites.[17] This connection suggests that the second source here is probably closely related to the E source in Genesis, the same one that described the death of Rachel (grandmother of Ephraim).

The Origin of Alternative Accounts of Events

Here it is necessary to reexamine one of the most basic tenets of scholarly thought concerning the origin and evolution of documentary sources. This tenet is well expressed in a recent paper by Erhard Blum on the coherence or otherwise of the Priestly source in Genesis: “If diachronically distinct material interrupts an otherwise coherent and continuous context, this speaks for the independence of the context in relation to the material causing the interruption.”[18]

This point demonstrates an expectation that the inserted material is “diachronic” in the sense that it is older or younger than the source that it interrupts. This expectation leads to huge problems, which Blum uses to attack the integrity of the P tradition as an independent source. For example, he argues that P’s account of the divine appearance at Bethel (Genesis 35:11–15) is a doublet of the interleaved J/E accounts in Genesis 28:11–19, and dependent on them, in the sense that P reinterpreted the encounter of Genesis 28:11–19. The basis of the argument is the similarity of the ritual and the divine promises in the two encounters. However, it overlooks a fundamental difference– Genesis 28 describes a vision on the way to Paddan Aram, while Genesis 35 describes one on the way back. In fact, E describes Jacob stopping at Bethel on the way to Paddan Aram as well as on the way back. In contrast, P doesn’t know about Jacob’s experience on the way to Paddan Aram, so the ritual and the divine promises must be included in his account of what was really Jacob’s second visit to Bethel, on the way back.

The root of this problem is Blum’s assumption of a “diachronic” model, where one tradition must necessarily precede the other. Alternatively, P and J/E could report similar events based on independent recollections that were preserved until the time of their merger. For example, William F. Albright suggested that because the documentary sources were formed over a period of time, their ages could overlap rather than having a simple diachronic relationship: “Since many traditions embedded in our three sources were formed and even phrased at different times, we have a staggered chronological relationship between them which greatly enhances their historical dependability.”[19]

Therefore, rather than being formed at different times, we should consider the alternative proposition that the traditions were formed alongside one another, but in different places or cultural contexts, which kept them separate even though they existed at the same time. For comparison, evolutionary science tells us that the basic requirement for the development of incompatible breeding populations is the geographical or behavioural separation of subgroups of a population, so that they can each develop their own self-propagating group.[20]

In the case of the Pentateuch and the subsequent historical books (the “Former Prophets” of the Hebrew Bible), it is clear that these narratives developed within the tribal society of Israel. Therefore, it is natural to look for a tribal basis of alternative recollections of events that were developing simultaneously. This tribal aspect of the documentary sources has been recognised by some scholars, who identify the Yahwist (J) with the tribe of Judah, and the Elohist (E) with the tribe of Ephraim.[21] But, in addition, the Priestly source should also be attributed to a distinct community within the tribe of Levi. The tribes were geographically separated after the conquest of Canaan, but before that they were socially separated, even when they were living as a single nomadic community. We can trace this tribal rivalry all the way back to their origins in the family of Jacob.

The separation of the tribal history of Ephraim probably began when the other brothers sold Joseph into slavery in Egypt. Here, I am assuming that this story in Genesis 37 is an account of real events. And one of the best reasons for believing this is the evidence that the story (as presently laid out) was composed by interfingering two slightly different accounts from E and J.[22] In other words, the two slightly different accounts corroborate each other in the same way that truthful but slightly varying eye-witness statements do in a law court.

It was in Egypt that Joseph found success and began his own family tradition. Therefore, it should not be surprising that this tradition included the beginnings of a separate tribal history, which was passed on to the chosen descendant, Ephraim. This importance of family histories is an overlooked aspect of the ancient concept of the birthright. The birthright conferred ownership of the family tradition, which therefore passed to Ephraim rather than Manasseh. Likewise, when Judah was recognised as preeminent over his elders (Reuben, Simeon, and Levi), his tribe inherited the J account.

Many scholars dispute the existence of E as a genuine distinct source, arguing it is just a supplement to J.[23] For example, it doesn’t have its own origins account. But that is exactly what we would expect from the tribal origins of the documentary sources. There is only room for one oral history in a single close-knit family, but as siblings separate into their own families, clans, and tribes, some may develop their own oral accounts. Hence, the family history of Ephraim (E) reaches only as far back as the knowledge its founder (Joseph) had about the experiences of his great-grandfather (Abraham) in Canaan.

Evidence for Documentary Continuity

Almost as important as the evidence for distinct sources (based on repeated accounts of events with differing details) is the evidence for documentary continuity. However, documentary continuity is expressed differently in P and the saga sources, reflecting their different functions. These differences need to be understood to appreciate the continuities of the distinct sources.

For example, the documentary continuity of the P source in Genesis is expressed in the repeated reporting of genealogical information. Whether or not the toledot genealogical “formula” itself was an addition by the redactor, it remains true that an interest in genealogical details is a consistent characteristic of the P document.[24] Another particular focus of P is on accounts of covenant relationships. Three of these covenants (creation, rainbow, circumcision) were regarded by Wellhausen as “preludes” to the Mosaic covenant.[25] Thus, the six-day account of creation forms the context of humankind’s commission to fill the earth, and this commission is reinstated after the Flood, before being narrowed into the national and tribal commissions of the patriarchs.

Covenant agreements also exist within the J source in Genesis, such as God’s promise of descendants to Abraham in Genesis 15. However, that particular covenant was “acted out” in a way that made it particularly suited to oral transmission. In contrast, the covenants in P needed to be recorded in writing because they required specific human observance. For example, they include three agreements between human parties alone (see Table 1). It is likely that these agreements were preserved on cuneiform tablets, since this type of record was commonly used in Mesopotamia to record legal agreements. Cuneiform was the principal medium of international diplomatic communication up until the time of Moses.[26]

Priestly narrative |

Divine names |

Legal requirement |

| Covenant of creation | Elohim only | First great commission |

| Covenant of building the ark | Elohim only | Promised reinstatement |

| Covenant of the rainbow | Elohim only | Reinstated commission |

| Covenant of circumcision | All three | Circumcision law |

| Abraham property purchase | None directly | Land agreement |

| Isaac’s commission to Jacob | El Shaddai | National commission |

| Covenant promise to Jacob | Elohim only | National commission |

| Treaty, Pharaoh and Joseph | None | Land agreement |

| Blessing to Joseph and sons | El Shaddai | Tribal commission |

| Joseph burial instructions | None | Last will & testament |

Table 1. Covenant agreements in Genesis that were most suited for recording in writing

Source continuity is also demonstrated by the presence of distinct words and phrases not used in the other sources. This allows the documents to be distinguished even in places where there is less clear evidence from duplicate accounts of events. For example, there are hundreds of descriptions of dying in the Pentateuchal documents, but only P uses the Hebrew word for “expire” (11 times) or the phrase “gathered to his people” (11 times) to describe death. In turn, only J uses the word sheol to describe the place of the dead (6 times).[27] Similarly, in describing procreation, only the P source uses the expression “be fruitful and multiply” (12 times), whereas only J uses the expression “to know” a woman (6 times). J also uses the expression “to lie with” 11 out of 13 times (the other two in E).[28]

Divine names represent a specific example of distinct vocabulary in the different sources, but this criterion has often been misunderstood. As Richard Friedman explains, it is not simply that the different documents use different names for God, but that these differences point to different historical views (on the part of their authors) about when the divine names were first revealed.[29] For example, when J quotes dialogue, his characters do not necessarily use the name Yahweh if they were living in a different culture from the people of God. For example, when Joseph refers to God while living in Egypt he uses the more generic word Elohim, even in the J source (Genesis 42–45). By contrast, J always uses the name Yahweh in narration,[30] since he believes that this name was revealed to humankind from the beginning (Genesis 4:26).

Strictly speaking, this cannot have been true, because the name Yahweh is Hebrew, which was not spoken where the primeval history is set, in Mesopotamia. But if the J tradition was passed down orally, the original name of the true God must have been updated over time to make the story more intelligible for later listeners.[31] In that case, later guardians of the J tradition would not actually have known what name the originator of this tradition used for God.

In contrast, the E and P sources both claim that the name Yahweh was not known until the time of Moses. For example, Exodus 6:2–3 (P) spells this out explicitly: “And God spoke to Moses and said to him, “I am YHWH. And I appeared to Abraham, to Isaac, and to Jacob as El Shaddai, and I was not known to them by my name YHWH.”[32] As a result, the P source never uses the divine name Yahweh in dialogue until the time of Moses, because its characters could not have known that name. However, the P author occasionally uses the name Yahweh in narrative if he wants to emphasise the continuity of revelation by the same God to the patriarchs and to Moses. For example, in the revelation to Abraham (Genesis 17:1), he says, ‘YHWH appeared to Abram and said to him, “I am El Shaddai.”

Two Accounts of Creation

The above discussion has focused largely on the stories of the patriarchs and the subsequent history of Israel. These alternative accounts involve the sources J, E, and P, and are best explained by alternative tribal records of these events. But what about the alternative accounts of origins in Genesis 1 (up to Genesis 2:4a) and Genesis 2 (verses 4b to 25)? Firstly, these accounts describe events that evidently occurred long before the origins of Israel itself. Secondly, these accounts seem to be describing completely different creative events, rather than being duplicate accounts of the same creation.

There is an alternative “fundamentalist” view that the creative acts of Genesis 1 and 2 were consecutive, implying that the two accounts should be harmonised into a single coherent story. This kind of harmonisation might seem like a harmless simplification of the text for non-scholarly readers, but if the two creation accounts are actually describing creation from different perspectives, harmonising them into a single story is misleading and liable to cause misunderstanding and misinterpretation. In fact, this can be identified as a major cause of the naïve “creationist” approaches to the origins stories of Genesis that we are attempting to avoid.

Unfortunately, similar views have been adopted by conservative scholars such as John Walton and C. John Collins in their books and commentaries on Genesis.[33] These claims cannot be discussed in detail here, but a major argument against them is that the views of these scholars are themselves contradictory, since one identifies Genesis 2 as an elaboration of Genesis 1, while the other views the two accounts as sequential.[34]

The Documentary Hypothesis avoids these problems by identifying the very different accounts of creation in Genesis 1 and Genesis 2 as the origins stories of two different communities. But before we ask what the different styles of Genesis 1 and 2 imply about the origins of these accounts, we need to examine one other important example of a Genesis narrative with alternative versions of events.

One or Two Accounts of the Flood?

The story of Noah’s Flood was a major problem for the redactor of the Pentateuch because it was evidently not credible that the cosmic Flood happened twice. This might seem obvious, but the existence of two creation stories shows that this was not necessarily a given. Nevertheless, the redactor here adopted a different approach, finely interleaving two sources (P and J) to create a single account. The success of the redactor in this objective can be seen by comparing Genesis with the Mesopotamian accounts (see Table 2).

The evidence in this table shows that the complete biblical Flood Story has closer similarities with the Mesopotamian versions than either of the proposed biblical sources. Furthermore, the similarity seems to be strongest with the most recent Mesopotamian version of the Flood Story in the standard (first millennium) version of the Gilgamesh Epic. This is indicated by the + signs in the table, meaning sections of narrative that are definitely present, relative to Xs, meaning sections known to be missing from structurally complete parts of the tablets. In contrast, question marks indicate sections whose presence is unknown due to damaged or missing tablets.

Event in the story |

Genesis Source |

Mesopotamian

|

|||

| 1. The Flood was caused by divine plan. | J |

|

|||

| 2. A reason is given for the Flood. | P, J |

|

|||

| 3. The hero is warned by divine revelation. | P |

|

|||

| 4. Hero instructed to build a large boat of a given size. | P |

|

|||

| 5. The hero is attentive and obeys the divine command. | P, J |

|

|||

| 6. Animals as well as people are loaded on the boat. | P, J |

|

|||

| 7. The hero is instructed to enter the boat. | J |

|

|||

| 8. The door is closed. | J |

|

|||

| 9. Duration of rain and floodwater rise is described. | P, J |

|

|||

| 10. The death of humankind is described. | P, J |

|

|||

| 11. The end of the rain is described. | P, J |

|

|||

| 12. The grounding on a mountain is described. | P |

|

|||

| 13. The hero opens a window. | J |

|

|||

| 14. Duration of waiting for waters to abate is described. | J |

|

|||

| 15. Hero sends out birds to test for abating of the Flood. | J |

|

|||

| 16. Hero offers sacrifices of worship after he is delivered. | J |

|

|||

| 17. Divine appreciation of the sacrifice is described. | J |

|

|||

| The hero receives a divine blessing. | P |

|

Table 2. Episodes in the Flood Story attributed to P and J, compared with episodes in the Mesopotamian accounts. Biblical sources: J =Yahwist, P = Priestly. Mesopotamian: G = Gilgamesh Epic; A = Atrahasis Epic; S = Sumerian Flood Story. Modified after Wenham.[35]

The close match between the complete biblical Flood Story and the account in the Gilgamesh Epic suggests that the redactor had access to the epic at the time he amalgamated his sources, almost certainly during the Jewish exile in Mesopotamia. The observation that the biblical account closely follows the Mesopotamian epic, but also retains numerous duplicate sections, is critically important. It implies that the sources themselves predated the exile. If the biblical Flood Story was a new composition during the exile, based directly on the Gilgamesh Epic, there would be no reason for it to preserve an origin from the interleaving of two source documents. However, it is equally unlikely that the overall story was created directly from two Mesopotamian sources, because the P source has such a strong Israelite genealogical imprint in it.

Additional evidence that the Flood Story was composed by interleaving two distinct source documents comes from characteristically different word usages in these two sources. The clearest use of such distinct language is seen in the P and J creation narratives, but the same distinct word usages can also be seen in shorter fragments of the Flood Story attributed to distinct P and J sources. These distinct patterns of word usage were summarised by Denis Lamoureux,[36] as shown in Table 3. The first section lists stylistic features and idiomatic expressions shared by the P accounts of Creation and Flood, while the second compares the J accounts. This impressive set of consistent expressions provides strong evidence in support of the Documentary Hypothesis, but raises the question of why the redactor should have wanted to retain two accounts of the Flood by interfingering them in this way.

Word/expression |

P Creation |

P Flood |

| Elohim | 35x | 16x |

| The deep | 1:2 | 7:11, 8:2 |

| Face of the waters | 1:2 | 7:18 |

| According to its/their kind | 1:11–12, 21–25 | 6:20, 7:14 |

| Wild and domesticated | 1:24–25 | 7:14, 21, 8:1, 9:10 |

| Birds referred to as “wing” | 1:21 | 7:14 |

| Swarm | 1:20–21 | 8:17, 9:7 |

| Creeping thing of the ground | 1:25,30 | 6:20, 8:19 |

| Creeping thing creeping | 1:26 | 7:14, 8:17 |

| Humankind in God’s image | 1:26 | 9:6 |

| Male and female | 1:27 | 6:19, 7:9,16 |

| Be fruitful and increase | 1:28 | 8:17, 9:2, 9:7 |

| Fish of the sea | 1:28 | 9:2 |

| It will be food for you | 1:29 | 9:3 |

Word/expression |

J Creation |

J Flood |

| Yahweh | 29x | 10x |

| Anthropomorphic deity | 2:8, 3:8,21 | 6:6, 8:21 |

| Rain | 2:5 | 7:4,10, 8:2b |

| Face of the ground | 2:6, 4:14 | 6:7, 8:8,13b |

| Evil | 2:9,17, 3:5,22 | 6:5, 8:21 |

| Man and woman (of animals) | 2:23–24 | 7:2 |

| Curse/cursed | 3:14,17, 4:11 | 8:21 |

| Offering | 4:3–5 | 8:20 |

| Breath of life in “nostrils” | 2:7 | 7:22 |

Table 3. Distinct word usages in the P and J accounts of Creation and Flood.

The best explanation is that the redactor wanted to use distinct information that the two sources brought to the overall account. For example, P contained genealogical and chronological information that tied the Flood Story to the overall structure of Genesis. On the other hand, J contained vivid descriptive detail that helped fill out details of the story. A list of these interleaved sections is presented in Table 4. This suggests that the genealogy of Noah (italics in Table 4) was cut into pieces and narrative sections were inserted between them.

| 6:9–10 | This is the account of Noah. Noah was a righteous man, blameless among the people of his time, and he walked with God. Noah had three sons: Shem, Ham and Japheth. |

| 6:11–7:5 | Account of how God told Noah to construct the Ark to be saved from the Flood. |

| 7:6–7 | Noah was six hundred years old when the floodwaters came on the earth. And Noah and his sons and his wife and his sons’ wives entered the ark to escape the waters of the Flood. |

| 7:8–10 | Account of how pairs of animals came to Noah and entered the ark. |

| 7:11–12 | In the six hundredth year of Noah’s life, on the seventeenth day of the second month—on that day all the springs of the great deep burst forth, and the floodgates of the heavens were opened. And rain fell on the earth forty days and forty nights. |

| 7:13–9:17 | Account of Flood, including entry into the Ark, the advance and retreat of the waters, the exit from the Ark, the sacrifice of burnt offerings, and the new covenant between God and Noah. |

| 9:18–19 | The sons of Noah who came out of the Ark were Shem, Ham and Japheth. Ham was the father of Canaan. These were the three sons of Noah, and from them came the people who were scattered over the earth. |

| 9:20–27 | Account of Noah’s drunkenness and the cursing of Ham. |

| 9:28–29 | After the flood Noah lived 350 years. Altogether, Noah lived 950 years, and then he died. |

Table 4. Attribution of the Flood Story to distinct genealogical and narrative sources.

The Coexistence of Independent Primeval Histories

The best explanation for all of these features is that the accounts of primeval history, including the Flood stories in Genesis 6 to 9, were brought from Mesopotamia by the patriarchs, were incorporated into distinct histories during the early evolution of the Israelite tribes, and were recombined into a single narrative during the Babylonian exile. But, here, a major problem arises. If the documentary sources of the Pentateuch represent alternative accounts of events passed down as separate tribal histories, how could alternative accounts of the Creation and Flood be inherited and preserved by one man (Abraham) before the origins of the Israelite tribes from the sons of Jacob?

The most logical answer has already been hinted at—one of these traditions must have been written and the other oral, in order to preserve their distinct integrity. If this explanation seems speculative, it is nevertheless well supported by the character of the two sources (J and P). The primeval J source is almost always personal, dramatic, and anthropomorphic in its description of God. This style is present in all of its major narratives, including the Garden of Eden, the Fall, the murder of Abel, the Flood, the Tower of Babel, and the lives of the Patriarchs. In contrast, the P source is cosmic in its view and generally impersonal. P’s interest in individuals is primarily genealogical, and it has a particular interest in treaties and covenants that would normally have been written down. The P account of the patriarchs is famously lacking in detail. For example, the absence of an Isaac narrative has often been noted.[37] But this is exactly what we would expect from a written source that was preserved by nomadic patriarchs who may even have been illiterate, but who could appreciate the importance of preserving venerated ancient inscriptions, even if they could not understand them.

This issue of reverence (or lack thereof) for ancient traditions is at the heart of the Jacob and Esau stories. The biblical portrayal of Esau is of a person who cared nothing for his birthright as the inheritor of important ancient records; he reputedly sold them for a bowl of broth. On the other hand, it is evident that (for all their faults) Rebecca and Jacob understood this heritage, which is well expressed by the words uttered by the Archbishop of Canterbury as he presents the Bible to the British monarch during the coronation: “We present You with this Book, the most valuable thing that this World affords.”

We can see from the Genesis account that Jacob received no tangible benefit by buying the birthright and stealing the blessing of the firstborn from Esau; he obtained all of his worldly resources by working for Laban. This shows that the birthright and the blessing were primarily cultural or spiritual benefits, which God would presumably have given to Jacob anyway if he had not stolen them (see Genesis 48:19).

Divine Names and the Transmission of Sources

Having outlined a model of alternative written and oral accounts of the primeval history, it is necessary to consider how these traditions could have been preserved and transmitted, to reach us in their present state. A credible explanation for this process is an important step in establishing the feasibility of the model.

As is well known, divine names are frequently compounded in human names, thus revealing the names of the major gods at different times in history. For example, the name “Israel” is compounded from the divine name El and means “He wrestles with God”; while “Elijah” is compounded from both El and Yahweh, and means “My God is Yah(weh).” However, no names compounded with Yahweh are known before the time of Moses, showing that this name really was a new revelation to Moses. But, unlike P and E, the J source lacked any account of the revelation of this name to Moses. Therefore, the transmitters of the J tradition evidently assumed that the name Yahweh had always been the name of the true God, and they updated earlier divine names with Yahweh. (The name used in Genesis 2–3 is Yahweh Elohim, but this is generally attributed to the redactor constructing a semantic bridge between the Elohim of Genesis 1 and the Yahweh of Genesis 4).[38]

The usages of the divine name El can tell us quite a lot about the origins and evolution of the documentary sources of Genesis. For example, there are approximately fourteen usages of the name El in Genesis (depending on exactly how we count them), spread across all three documentary sources. This spread is consistent with El being the actual name for God used by the patriarchs. The majority are in compound names, the most common of which is El-Shaddai, but also El-Roi, El-Olam, and El-Bethel. These (comparatively rare) usages of El are vastly outnumbered by the usage of Yahweh in J and Elohim in E. Nevertheless, the multiple patriarchal names for God compounded from El may be the basis of the plural form of the generic word for God (Elohim) used in the final form of the Elohist saga.

In comparison with these compounded forms of El, there are four rare cases in E where the name El is preserved by itself. Three of these cases involve God speaking to Jacob, for example, “I am El of Bethel” (Genesis 31:13); “Get up, go to Bethel and live there and make an altar to El who appeared to you” (Genesis 35:1); and “I am El, your father’s God” (Genesis 46:3). The fourth case occurs when Jacob recites back what God just told him (Genesis 35:3). In addition, there is one case in J where the name El is preserved. This occurs in the prophecy of Jacob to his sons (including Joseph), when he says: “From El of your father who will strengthen you, and by Shaddai, who will bless you” (Genesis 49:25). However, it seems that the name El-Shaddai has been separated here into its component parts for poetic effect, and this form based on El-Shaddai is supported by the usage in Exodus 6:3 (P), where God says, “I appeared to Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob as El Shaddai.” This suggests that El-Shaddai was the normative compounding of El during the patriarchal period.

The conclusion we can draw from all of this evidence is that El was the name of God actually used by Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, but it was translated in all three sources to the later usage of Elohim, except where it was “protected,” either by compounding with another name that the later transmitter of the tradition wanted to preserve, or by being used in the very words of God, which were sacrosanct.

In comparison with the above, there is no preserved usage of the name El in the primeval history, which took place in Mesopotamia (Genesis 1–11). But we must remember that this history was based on two completely separate J and P accounts. We would not expect any early divine name to be preserved in the J source, since we know that all divine names there were replaced with Yahweh. In contrast, if the P source was written, a pre-Abrahamic usage of divine names could have been preserved through the patriarchal period.

By the time of Moses (mid-second millennium), cuneiform had become an international diplomatic script, used even in Egypt, as demonstrated by the Amarna letters. Raised in the Egyptian court, Moses could undoubtedly read cuneiform, so he could have read the primeval Mesopotamian history of Israel, including the Flood story. However, in Exodus all writing except the two tablets of the Decalogue was written on scrolls (Exodus 17:14; 24:7; 32:32). It is almost certain that this involved (cursive) hieratic script, as this was the only script that was widely used in the southern Levant for writing on scrolls. Hence, this is the point when cuneiform documents brought by Abraham from Mesopotamia were probably transcribed into hieratic Egyptian, to make them consistent with the newly written (P) account of Exodus.

Moses was probably familiar with oral accounts circulating amongst the Israelites that referred to God by several names compounded with El. In addition, he probably knew of the Mesopotamian names for God used in the Flood story. Hence, when God appeared to Moses at the burning bush, the names for God in Israelite tradition were many and varied, so that Moses’ question about God’s name was far from an idle one: “Suppose I go to the Israelites and say to them, ‘The god of your fathers has sent me to you,’ and they ask me, ‘What is his name?’ Then what shall I tell them?” (Exodus 3:13). In response, God revealed his new name “Yahweh,” which Moses could have used to translate all of the divine names in the written primeval history.

We know that the Egyptians were able to render the divine name Yahweh in hieroglyphics phonetically, because it was used on the Soleb inscription (see Figure 1 left, represented by the Gardiner signs M17A, O4, V4 and G1).[39] However, Moses evidently did not do this, since the Priestly source in Genesis does not use Yahweh. Instead, Moses probably rendered the names of the Mesopotamian gods using the generic Egyptian word for God, netjer. This is expressed by a flag-like hieroglyphic (and therefore hieratic) sign (R8 in the Gardiner sign list).[40]

Figure 1. Phonetic spelling of the names Yahweh and Aper-El in hieroglyphics. After Hen[41] and Zivie.[42]

Somewhat more complex is the question of how the patriarchal name El was rendered in Egyptian signs. The answer is found in several hieroglyphic tomb inscriptions, where the divine name El is compounded as part of various Canaanite Egyptian names. The example in Figure 1 (right) is the name Aper-El, from Tomb 68 at Saqqara, where the signs for El are comprised from ‘i’ (M17) and ‘3’ (G1), as shown in numerous examples by Hoch.[43] The G1 sign is the early form of Alef, contributing the sound “al.”[44] This appears to be an archaic phonetisation, before the proto-alphabetic letters “a” (as in alpha) and “l” (as in lambda) were derived from the hieroglyphic signs F1 and V1.[45]

During the Israelite monarchy, when Hebrew written documents were being composed, the influence of Egypt was starting to decline. However, the hieratic script underwent a renaissance during the Judean monarchy (8th–7th centuries BC).[46] This was probably when the hieratic P document was translated into Hebrew, and the divine names would then have been recovered by comparison with the orally transmitted traditions of J and E, which were probably written in Hebrew during the time of Solomon. Assuming that Deuteronomy is the last speech of Moses, it must originally have been transcribed in hieratic, but was translated into Hebrew near the end of the Judean monarchy (after its rediscovery during the reign of Josiah). This explains why the Hebrew of P is later than J and E, but earlier than D.[47]

Mesopotamian Origins of the Biblical Creation Stories

Having explored how distinct creation narratives could have been passed down in the history of Israel, it is also necessary to discern their origins in Mesopotamian history. The clearest evidence for the Mesopotamian origins of the creation stories comes from the J account (Genesis 2), which has many features in common with the mythology of the Mesopotamian city of Eridu and its patron deity, Enki. However, Genesis 1 also contains more subtle evidence of a Mesopotamian source (to be discussed below).

One of the major common themes in the biblical and Eridu origins accounts is the idea of one man who acts in a priestly capacity in a sacred space (such as the garden of Eden). In Mesopotamian mythology, this man was Adapa, priest of Enki at Eridu, whose story is told in the Myth of Adapa. [48] The story relates how Adapa went fishing to provide offerings for the Eridu temple. Remains of fish were indeed found on the altar of a primitive temple in Eridu, probably dating to the fifth millennium BC.[49] While Adapa was fishing, the south wind created a storm and sank his boat. But as he was drowning Adapa cursed the south wind, breaking its wing. As a result, he was summoned to heaven (presumably after his death) in order to justify his actions. However, due to intercession by Adapa’s patron deities (at the direction of Enki, God of Wisdom), the God of Heaven was placated and went so far as to offer Adapa the Bread of Life. However, Adapa had previously been warned by Enki not to accept any food, as it would be poisoned. Therefore, he declined the bread of heaven, and consequently lost the chance of eternal life, in a way that somewhat parallels Genesis 2.

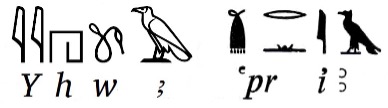

Another strong similarity between these traditions is a concern with the rivers of Mesopotamia. Genesis 2 describes the Garden of Eden as situated where a river divides into four, and names two of these rivers as the Tigris and Euphrates. Eden (Edin) is the Sumerian word for the plain of Mesopotamia,[50] therefore identifying the most likely site of Eden as the confluence of the Tigris and Euphrates at the southeast end of the plain. Similarly, the cult of Enki at Eridu was particularly associated with the Tigris and Euphrates, which are typically shown in the iconography of Eridu (see Figure 2) as originating in two flowing vases held by Enki, who is also the god of subterranean waters. In other depictions of Enki, fish are seen jumping from the streams of water, emphasising their life-giving qualities.[51]

Figure 2. A human worshipper in typical Sumerian gown (Gudea) is introduced by his patron god to the great god Enki, seated on his throne and holding overflowing vases. Modern impression of a late third millennium seal. Louvre Museum.

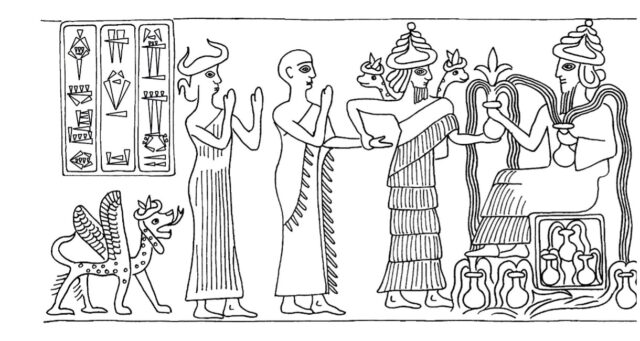

This idea of Eden as watered by rivers and canals is also seen in several early cylinder seal impressions from the city of Ur. The examples shown in Figure 3 were excavated by Leonard Woolley, and show both arable lands and fish between two bounding rivers. These depictions connect the biblical picture of God making a garden in Eden with the Sumerian concept of Enki carefully creating the agricultural landscape of Sumer (Enki and the World Order).[52] Similar parallels are found between the biblical description of Adam being made from the dust of the earth and the Mesopotamian idea of humankind being made from the clay of the ground.[53]

Figure 3. Seal impressions from the early third millennium, showing signs for the plain of Sumer, “Edin.” University Museum, Pennsylvania and British Museum. After Legrain.[54]

In contrast to the Eridu mythology of Genesis 2, the ancient city whose mythology is by far the closest to the creation story of Genesis 1 is Nippur. The patron deity of Nippur was Enlil, literally Lord-air/wind/breath, who along with Enki and the God of Heaven (An or Anu) made up a Sumerian “Trinity” of the ancient principal gods of the Sumerian pantheon. This preeminence is demonstrated by the consistent appearance of these three gods as the principal deities involved in all versions of the Flood Story (as discussed below).

A notable feature of the mythology of Nippur was the tradition that Enlil had separated the earth from the heavens, thus creating his own domain of the air between heaven and earth.[55] When we couple this idea with the part of Enlil’s name, lil, meaning wind or breath, we have a very similar picture to Genesis 1:2, where the wind of God was blowing over the face of the primeval waters before the beginning of creation, and likewise blowing over the face of the chaotic waters of the Flood in Genesis 8:1. These images are both from the biblical P document, but their origins most likely go back to a Mesopotamian priestly source from the third millennium BC.

The Preservation of Mesopotamian Origins Stories

Finding linkages between the Genesis creation stories and ancient Mesopotamian cities and their patron gods is clearly important. But if the creation stories of Genesis were derived from Mesopotamian sources, why do we not find closer parallels to Genesis in Sumerian literature? There are two likely reasons for this disappointing lack of evidence. The first concerns the purpose of writing itself. Contrary to our natural assumptions, writing was not invented to record important religious or mythological ideas, but as a book-keeping tool. This is very clear from the early (fourth millennium) tablets found at the city of Uruk, which are almost exclusively administrative in nature.[56]

The only fourth millennium tablets that are not administrative are systematic word lists that appear to have been used in scribal education. Furthermore, when the first literary tablets appear about 500 years later, they seem to be primarily or exclusively associated with scribal schools. These tablets were excavated from the mounds of Tell Fara (ancient Shuruppak) and Tell Abu Salabikh (possibly ancient Eresh). One of the most complete literary works found in these scribal schools was an ancient set of proverbs usually referred to as the Instructions of Shuruppak (the eponymous king of his city).[57] We know that this work was used as a scribal exercise because a small practice tablet was found, bearing only the first three lines of the introduction:

On a faraway day, indeed on a faraway day

On a faraway night, indeed on a faraway night

In a faraway time, indeed in a faraway time…[58]

The repetitive nature of this introduction perfectly illustrates why its copying was a favourite exercise for beginners. Indeed, the fact that a list of proverbs is the earliest significant literary work suggests that Sumerian scribes were not yet ready for religious narratives requiring complex grammatical constructions. These only appear hundreds of years later.

The second reason for a lack of Mesopotamian “versions” of Genesis is political interference in the traditional religion of Mesopotamia. Throughout the third millennium BC, the city of Nippur was the religious centre of Mesopotamian civilisation, and both Sumerian and Semitic rulers are recorded as building or renovating the temple of Enlil at Nippur.[59] However, towards the end of this period there were several strenuous efforts by both Semitic and Sumerian kings to promote themselves to divine status. This threatened the traditional religion of Mesopotamia and tended to corrupt its mythology. The first of these periods occurred when Semitic warrior kings from northern Mesopotamia conquered Sumer, establishing the world’s first empire at the city of Akkad.

The Akkadian empire had a relatively short duration of around 100 years, and according to a well-known lament called the Cursing of Akkad, its fall occurred when Mesopotamia was invaded by barbarians from the Iranian mountains.[60] The lament claims that this invasion was a judgement by the principal god Enlil, in response to the demolition of his temple at Nippur by King Naram-Sin of Akkad. Some scholars have questioned the historical accuracy of the Cursing, pointing out that after its demolition, the temple of Nippur was rebuilt by Naram-Sin’s son, several decades before the collapse of the empire.[61] However, administrative tablets associated with the rebuilding process suggest that the rebuilding was an attempt to secularise the temple institution, by introducing the worship of the sun-god to a temple previously devoted to Enlil.[62]

The fall of Akkad was followed by over a hundred years of anarchy, from which Mesopotamian civilisation finally emerged when a new dynasty was founded at Ur (the so-called 3rd dynasty of Ur). The first king of the Ur III dynasty, Ur-Nammu, successfully conquered most of southern Mesopotamia, but then died unexpectedly in battle.[63] Such an inauspicious event would have undermined the stability of the new dynasty, and this probably provoked his successor, Shulgi, to undertake various strategies to bolster his position.

Shulgi proclaimed his own divinity and made a conscious attempt to use Sumerian literature as propaganda to reinforce his claim. In fact, Piotr Michalowski has argued that in composing material for court performance, Shulgi was destroying oral traditions that had been passed down for centuries. Thus, in addition to proclaiming himself a god, “He also wiped clean the literary slate of the land, replacing the old Early Dynastic mythological literature with a whole new corpus, much of which was focused on the person of the country’s ruler, that is on himself.”[64] This process of textural corruption explains why Sumerian literature from the early second millennium no longer retains a true picture of Sumerian religious origins, despite an ongoing fascination with epic tales about the earlier semi-mythical Sumerian kings.

The Significance of the Gilgamesh Cycle

One of Shulgi’s strategies to bolster the status of his dynasty was the commissioning of a new version of the Sumerian King List.[65] An earlier version of the King List probably existed from the preceding Akkadian empire, and included the legendary ancient kings of Uruk: Enmerkar, Lugal-banda, and Gilgamesh. By connecting his own dynasty with Gilgamesh, Shulgi was able to promote his status as a divine king, because Gilgamesh had already (posthumously) achieved divine status by the end of the Early Dynastic period. This is demonstrated by several dedicatory inscriptions on ceremonial mace heads, which address Gilgamesh as a god.[66]

We know that there were early written stories about the famous kings of Uruk because one of the practice pieces from the Early Dynastic scribal school at Abu Salabikh is from a story about King Lugal-banda.[67] In addition, Gilgamesh himself was the subject of several artistic depictions during the Akkadian dynasty, suggesting that he was already the subject of oral or written traditions by this time.[68] However, it is believed that these stories were first formalised into a Gilgamesh Cycle during the reign of Shulgi (ca 2100 BC), partly as school material to train scribes for his administration, and also for performance at the royal court. Six different titles from the Gilgamesh Cycle are known from later scribal schools of the early second millennium at Nippur. Only hints of this material are known from the third millennium, but enough to suggest that the written versions originated then.[69]

One of the most important titles in the Gilgamesh Cycle, based on the linkages it creates with several other literary works, is the Death of Gilgamesh. This work describes how Gilgamesh fell ill and died, but because Gilgamesh was reputed to be two thirds divine and only one third mortal it was also necessary to explain why Gilgamesh had to die. This is done by describing a dream that Gilgamesh apparently experienced, consisting of a dialogue between the gods. In this dialogue, a speech by the god Enki explained that the Flood Hero (here called Zi-ud-sura) was the only man who would ever receive eternal life, and therefore even a demigod such as Gilgamesh must die. Because of the important link this speech provides with the Flood Story, it is quoted here from the translation of Jeremy Black:[70]

Enki answered An and Enlil:

“In those days, in those distant days,

in those nights, in those distant nights,

in those years, in those distant years,

after the assembly had made the Flood sweep over to destroy the seed of mankind,

among us I was the only one who was for life (?),

and so he remained alive (?)—

Zi-ud-sura, although (?) a human being, remained alive (?).

Then you made me swear by heaven and by earth,

… that no human will be allowed to live forever (?)…

Not only does this speech directly link the Flood Story to the Gilgamesh cycle, but as an explanation of why Gilgamesh must die it summarises Sumerian beliefs about the Flood, setting the Flood in primeval times using the mythological introduction quoted earlier.

The Death of Gilgamesh also confirms the claims in the major Mesopotamian versions of the Flood Story that the deluge was brought by agreement of the divine assembly, ruled over by the three principal gods, An, Enlil, and Enki. This triad of gods was preeminent throughout Mesopotamian history until the time of Hammurabi. Their Sumerian origins are demonstrated by the earliest proto-cuneiform writing from Uruk, and their names are written using the same cuneiform signs on important Akkadian inscriptions such as the Stele of Hammurabi.[71] The concept of the “divine assembly” or “divine council” is also quite widely known in the Bible. Hence, this provides an important link between Mesopotamian and biblical accounts, and may help us understand how Genesis and the Mesopotamian origins myths diverged from common early traditions.

The Transmission of the Flood Story

The Flood Story, as the strongest parallel between biblical and Mesopotamian views of reality, offers the best way to understand the relationship between them. The excerpt from the Death of Gilgamesh quoted above claims that the Flood was brought by the divine assembly, of which Enki was a part. However, in the Sumerian Flood Story it is clear that the assembly was ratifying the decision of An and Enlil: “A decision that the seed of mankind is to be destroyed has been made. The verdict, the word of the divine assembly cannot be revoked. The order announced by An and Enlil cannot be overturned.”[72]

The Sumerian Flood Story emphasises the joint rule of An and Enlil both in the quote above, and at several other places in the story. However, in the Semitic Atrahasis Epic, the role of An is played down and that of Enlil (Ellil, in Semitic pronunciation) is emphasised. In this epic, the Flood is only the last of a series of catastrophic attacks by the gods against humankind, and these are explicitly attributed at the beginning of the epic to the sleep of Enlil being disturbed by humankind’s noise. Furthermore, in each “disaster episode” it is Enki (Semitic Ea) who provides a way out for humanity. Hence, when Enlil plans the Flood as a “final solution” (end of tablet 2), it is he who is trying to coerce Enki into swearing an oath not to warn humankind, as Enki had previously done. In response, Enki objects to this coercion, and says that the Flood is “Enlil’s kind of work,” not his own.[73]

In the Atrahasis Epic the subsequent lines are lost, but in the Gilgamesh Epic Enki is said to have sworn the oath of secrecy. Nevertheless, in all of the Mesopotamian versions Enki manages to evade the oath and warn the Flood hero about the Flood by whispering his words to the walls of a reed hut, so that the wind (rather than he) carries the message through the walls of the hut to his devotee inside.

Based on these comparisons, I conclude that the process of evolution of the Mesopotamian versions of the Flood story was from an early form where all of the divine “Trinity” of supreme gods was part of the plan to bring the flood, to a later form where Enlil is essentially the sole instigator of the Flood, and Enki is the protector of humankind. Some biblical scholars have proposed a similar evolutionary process in the documentary sources of the biblical Flood story.

For example, Samuel Shaviv claimed that the P and the J versions of the biblical Flood story present two different divine viewpoints, in which P presents the view of Enki (saviour of mankind), whereas J presents the view of Enlil (instigator of the Flood).[74] However, this view contradicts the evidence from the creation accounts, where J clearly inherited the Enki tradition, whereas P was derived from the Enlil tradition. Furthermore, Shaviv’s view involves a selective reading of the Genesis Flood Story that distorts its meaning.

A straightforward reading of the Genesis text shows that the J account is more anthropomorphic than the P one, consistent with the differing styles of their creation accounts. For example, Yahweh is described as being grieved and regretting that he had made humankind before the Flood (Genesis 6:6), but also as smelling the pleasant aroma of Noah’s sacrifice after the Flood (Genesis 8:21). These examples show that feelings attributed to Yahweh are both judgmental and merciful, just as the P account describes God as warning Noah that He will destroy the earth (Genesis 6:13), as well as remembering Noah in the midst of the Flood (Genesis 8:1). Therefore, I reject the claims of Shaviv, and assert that both the P and J sources see God as the instigator of the Flood and the saviour of Noah, by instructing him to build and enter the Ark to survive the Flood. Therefore, I suggest that both biblical accounts of the Flood (J and P) separately modified their Mesopotamian source traditions into a monotheist viewpoint.

For the oral tradition (J), this change must have been made by Abraham, who understood that the supreme god El who revealed himself to Abraham embodied both of the divine players in the Flood story, Ellil and Ea (in Akkadian). This understanding that a single God could speak in plural terms was preserved in two of the J stories of origins, the Eden narrative (Genesis 3:22) and the Babel story (Genesis 11:7), despite the apparent singularity of the revelation of Yahweh to Moses (Deuteronomy 6:4).

As noted above, Moses probably translated the multiple divine names in the written version of the Flood story (Enlil and Enki), using the generic Egyptian title of God (Ntr in hieratic script), thus showing that both divine persons were one God. However, he still maintained the plural speech of God in creation (Genesis 1:26). Therefore, when the hieratic was translated into Hebrew, it was appropriate to use the plural form Elohim, based on Genesis 1:26 and the concept of the divine council also found in the psalms (e.g. Psalm 82).

The Need for a Falsifiable Theory of Origins

The above arguments provide only a rough sketch of the possibilities for understanding the Genesis creation stories as distinct Mesopotamian traditions that were passed down for thousands of years, most notably through Abraham and Moses, before their merger during the Babylonian exile. However, the most important aspect of this sketch is that it has the possibility of being tested. If it were not possible to express the ideas of Genesis 1 in cuneiform, hieratic, and Hebrew scripts, this would be an argument against the model presented.

This is the scientific basis for speculating on the origins of the Genesis creation texts, since scientific models are fundamentally based on their falsifiability. According to the book of Daniel, this concept was understood by king Nebuchadnezzar, who made the extreme demand that his wise men should recite to him the content of his dream (Daniel 2:5), in order to demonstrate their ability to interpret it (2:9b). In the same way, a viable theory of textual origins is important for validating textual interpretations. Therefore, since it is claimed that God’s word endures forever (Isaiah 40:8), it seems logical that the origins of God’s recorded words of creation should be sought with as much diligence as the material origins of the cosmos.

The conclusion of this investigation is that the origins accounts of Genesis were passed down directly from the earliest period of human civilisation in ancient Mesopotamia. There are good grounds for believing that these origins stories were inspired by God in Mesopotamia, either in the form of dreams (Genesis 1) or as symbolic descriptions of real experiences (Genesis 2–3).[75] They were not derived by “sanitising” corrupt myths, but are themselves the bedrock of truth, passed down by Abraham and Moses before their merger into the Pentateuch during the Babylonian exile. This evidence speaks for the reliability of these accounts, but also demonstrates their very ancient character. They cannot be comprehended by naïve fundamentalism, but must be understood by ongoing careful scholarship.

The author reports there are no competing interests to declare.

Received: 12/07/23 Accepted: 25/02/25 Published: 06/08/25

[1] Hugh Ross, Creation and Time (Carol Stream, IL: Navpress, 1994), 45, 154.

[2] Christoph Levin, “The Priestly Writing as a Source: A Recollection,” in Farewell to the Priestly Writing? The Current State of the Debate, ed. Friedhelm Hartenstein and Konrad Schmid (Atlanta, GA: SBL Press, 2022), 1–26.

[3] Benedict Spinoza, Tractatus Theologico-Politicus (1670), trans. R. H. M. Elwes, The Chief Work of Benedict Spinoza (London: George Bell & Sons, 1891).

[4] Jean Astruc, Conjectures sur les mémoires originaux, dont il paraît que Moïse s’est servi pour composer le livre de la Genèse (1753; Conjectures on the original accounts of which it appears Moses availed himself in composing the Book of Genesis, published anonymously).

[5] Burnett H. Streeter, The Four Gospels: A Study of Origins treating of the Manuscript Tradition, Sources, Authorship and Dates (New York and Toronto: MacMillan, 1924).

[6] Hermann Hupfeld, Quellen der Genesis und die Art ihrer Zusammensetzung: von neuem untersucht (Berlin: Wiegandt und Grieben, 1853), 195.

[7] Sidnie W. Crawford, “The Text of the Pentateuch,” in The Oxford Handbook of the Pentateuch, ed. Joel S. Baden and Jeffrey Stackert (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2021), 41–60.

[8] Wilhelm M. L. de Wette, Beiträge zur Einleitung in das Alte Testament (Contributions to the Introduction to the Old Testament; Halle: Schimmelpfennig, 1807).

[9] Wilhelm Vatke, Die Religion des Alten Testamentes nach den kanonischen Büchern entwickelt (Berlin: G. Bethge, 1835).

[10] Karl H. Graf, Die geschichtlichen Bücher des Alten Testaments: zwei historisch-kritische Untersuchungen (The historical books of the Old Testament: two historical-critical investigations; Leipzig: T. O. Weigel, 1866).

[11] Julius Wellhausen, Prolegomena zur Geschichte Israels (Berlin: Georg Reimer, 1883). Translated by John Sutherland Black and Allan Menzies as Prolegomena to the History of Israel (London: Adam and Charles Black, 1885), 9.

[12] Thomas B. Dozeman and Konrad Schmid (eds), A Farewell to the Yahwist? The Composition of the Pentateuch in Recent European Interpretation (Atlanta, PA: Society of Biblical Literature, 2006).

[13] Jan C. Gertz, “The Formation of the Primeval History,” in The Book of Genesis, ed. Craig A. Evans et al. (Leiden and Boston: Brill, 2012), 105–135.

[14] Joel S. Baden and Jeffrey Stackert (eds), The Oxford Handbook of the Pentateuch (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2021).

[15] Joel Baden, The Composition of the Pentateuch: Renewing the Documentary Hypothesis (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2012), 20.

[16] Richard E. Friedman, The Hidden Book in the Bible: The Discovery of the First Prose Masterpiece (San Francisco, CA: Harper, 1998).

[17] Nadav Na’aman, “The Settlement of the Ephrathites in Bethlehem and the Location of Rachel’s Tomb,” Revue Biblique (2014): 516–529.

[18] Erhard Blum, “Once Again: The Literary-Historical Profile of the P Tradition,” in Farewell to the Priestly Writing? 27–61.

[19] William F. Albright, From the Stone Age to Christianity: Monotheism and the Historical Process (Baltimore, MD: John Hopkins Press, 1940), 252.

[20] David Lack, Darwin’s Finches (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983).

[21] Richard E. Friedman, The Bible with Sources Revealed (New York: HarperCollins, 2003), 18–21.

[22] Baden, The Composition of the Pentateuch, 34–44.

[23] Baden, The Composition of the Pentateuch, 103–128.

[24] Blum, “Once Again,” 40–48.

[25] Wellhausen, Prolegomena to the History of Israel, 7.

[26] William L. Moran, The Amarna Letters (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1992).

[27] Friedman, The Bible with Sources Revealed, 9.

[28] Friedman, The Bible with Sources Revealed, 9.

[29] Friedman, The Bible with Sources Revealed,10.

[30] Friedman, The Bible with Sources Revealed, 10.

[31] Alan Dickin, “Recovering Genesis 1 from Scientific and Societal Misunderstanding,” Christian Perspectives on Science and Technology, New Series, 2 (2023): 28–57, https://doi.org/10.58913/ULGJ3154.

[32] Friedman, The Bible with Sources Revealed, 10.

[33] C. John Collins, Genesis 1–4: A Linguistic, Literary, and Theological Commentary (Phillipsburg, NJ: P&R Publishers, 2006); John H. Walton, The Lost World of Adam and Eve: Genesis 2-3 and the Human Origins Debate (Westmont, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2015).

[34] Alan Dickin, A Scientific Commentary on Genesis 1–11, 3rd edition (Amazon, 2021), 64–67.

[35] Gordon J. Wenham, “The Coherence of the Flood narrative,” Vetus Testamentum 28:3 (1978): 336–348.

[36] Denis O. Lamoureux, Evolutionary Creation: A Christian Approach to Evolution (Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock, 2008), Appendix 5.

[37] Blum, “Once Again,” 31.

[38] Friedman, The Bible with Sources Revealed, 35.

[39] Titus Kennedy, “The Land of the š3sw (Nomads) of yhw3 at Soleb,” Dotawo: A Journal of Nubian Studies 6:1 (2019): 175–192, https://doi.org/10.5070/D66146256.

[40] Alan H. Gardiner, Egyptian Grammar: Being an Introduction to the Study of Hieroglyphs, 3rd edn (Oxford: Griffith Institute, 1957; 1st edn 1927), 438–548.

[41] Racheli S. Hen, “Signs of YHWH, God of the Hebrews, in New Kingdom Egypt?” Entangled Religions 12:2 (2022), https://doi.org/10.46586/er.12.2021.9463.

[42] Alain-Pierre Zivie, “Tombes rupestres de la falaise du Bubasteion à Saqqarah, Campagne 1980–1981 (Mission Archéologique Française de Saqqarah),” Annales du Service des Antiquités de l’Egypte Le Caire 68 (1982): 63–69.

[43] James E. Hoch, Semitic Words in Egyptian Texts of the New Kingdom and Third Intermediate Period (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1994), 27–28.

[44] Thomas Schneider, “Etymologische Methode, die Historizität der Phoneme und das ägyptologische Transkriptionsalphabet, Lingua Aegyptia 11 (2003): 187–199.

[45] Gordon J. Hamilton, The Origins of the West Semitic Alphabet in Egyptian Scripts, The Catholic Biblical Quarterly Monograph Series 40 (Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock, 2024), 128.

[46] Orly Goldwasser, “An Egyptian Scribe from Lachish and the Hieratic Tradition of the Hebrew Kingdoms,” Tel Aviv 18:2 (1991): 248–253, https://doi.org/10.1179/tav.1991.1991.2.248.

[47] Friedman, The Bible with Sources Revealed, 7.

[48] Stephanie Dalley (ed.), Myths from Mesopotamia: Creation, the Flood, Gilgamesh, and Others (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1989), 182.

[49] Seton Lloyd, The Archaeology of Mesopotamia: From the Old Stone Age to the Persian Conquest (London: Thames and Hutton, 1978), 16.

[50] John A. Halloran, Sumerian Lexicon (Los Angeles: Logogram Publishing, 2006).

[51] Jeremy Black et al. (eds), Gods, Demons and Symbols of Ancient Mesopotamia: An Illustrated Dictionary (London: British Museum Press, 1998), 75.

[52] Jeremy A. Black et al. (ed.), The Literature of Ancient Sumer (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004), 215–225.

[53] Dalley, Myths from Mesopotamia, 25.

[54] Leon Legrain, Ur Excavations, vol. 3: Archaic Seal-Impressions (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1936), Plate 23, 25.

[55] Wilfred G. Lambert, Babylonian Creation Myths (Philadelphia, PA: Penn State University Press, 2013), 170.

[56] Hans J. Nissen, “The Archaic Texts from Uruk,” World Archaeology 17:3 (1986): 317–334.

[57] Bendt Alster, Wisdom of Ancient Sumer (Bethesda, MD: CDL Press, 2005).

[58] Robert D. Biggs, “The Abu Salabikh Tablets,” Journal of Cuneiform Studies 20 (1966): 73–89.

[59] Poitr Michalowski, “The Strange History of Tumal,” in Approaches to Sumerian Literature, ed. Piotr Michalowski and Niek Veldhuis, Cuneiform Monographs 35 (Leiden: Brill, 2006), 145–165.

[60] Benjamin R. Foster, The Age of Agade: Inventing Empire in Ancient Mesopotamia (New York: Routledge, 2015), 350.

[61] Henry W. F. Saggs, Babylonians (Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press, 2000), 75.

[62] Alan Dickin, From the Stone Age to Abraham: A Biblical History of the Ancient World (Seattle: Kindle Direct Publishing, 2021), 250.

[63] Piotr Michalowski, “Maybe Epic: The Origins and Reception of Sumerian Heroic Poetry,” in Epic and History, ed. David Konstan and Kurt A. Raaflaub (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2010), 7–25.

[64] Michalowski, “Maybe Epic,” 20.

[65] Piotr Steinkeller, “An Ur III Manuscript of the Sumerian King List,” in Literatur, Politik und Recht in Mesopotamien, ed. Walther Sallaberger et al., Orientalia Biblica et Christiana 14 (Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, 2003), 267–292.

[66] Albert T. Clay, Miscellaneous Inscriptions in the Yale Babylonian Collection, vol. 1 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1915).

[67] Robert D. Biggs, “The Abū Ṣalābīkh Tablets: A Preliminary Survey,” Journal of Cuneiform Studies 20:2 (1966), 73–88.