Reviewed by Ian Hore-Lacy, August 2010, updated January 2021.

(Faraday Papers 1–20 to date, review updated January 2021)

Faraday Institute for Science & Religion, Cambridge, UK.

This is a wonderful collection of papers, each four A4 pages, covering a range of topics relevant to ISCAST. Their diversity allows each author to write according to interest without any imposed editorial homogeneity, and in my view this enhances their appeal.

John Polkinghorne leads the way with an overview of ‘The Science and Religion Debate’ and how it has been expressed in argument and conversation. While most of us have read plenty along this line, he manages to bring a fresh treatment. A further paper by him on “The Anthropic Principle” extends the natural theology part of this to an excellent exposition of the matter, in simple language. It highlights the quandary of scientists who recognise the importance of the specific conditions for carbon-based life—the fine-tuning—but have no inclination to look outside science for any explanation.

Rodney Holder asks “Is the Universe Designed?” and usefully complements Polkinghorne’s anthropic principle paper, with more attention to critiquing arguments that the universe is not designed. He disposes of the multiverse explanation and outlines evidence supporting the Big Bang model.

Roger Trigg in “Does Science Need Religion?” gives a helpful philosophical outline of how science rests on major assumptions regarding the regularity and order of the physical world, rather than being autonomous. Denis Alexander then sets out four “Models for Relating Science and Religion” and suggests why the conflict model persists so disastrously today. The familiar complementary model where each is addressing the same reality from different perspectives is most useful, but not the be-all and end-all.

In “Miracles and Science” Denis Alexander notes that most of the founders of modern science did believe in miracles, and we need to be careful to use a biblical definition of the term. This might be “a sign of God’s special grace in a particular historical-religious context” that points to something. They may or may not have some natural explanation but are not just isolated anomalies which violate the laws of nature. The secular mantra that miracles would undermine science and its natural laws if they were true is misconceived. Closed minds ignore evidence. God transcends descriptive natural laws, most convincingly in Jesus’ resurrection.

Sir John Houghton answers the question, “Why Care for the Environment?” in measured terms regarding sustainability and his own specialty of climate change. Another paper with apologetic aspects is John Bryant on “Ethical issues in Genetic Modification”. He surveys the background and application of GM in both plants and animals, considering the ethical debates in relation to each. He concludes ‘that there are strong theological motivations’ for using it within ethically-defined limits.

A most helpful discourse on “Reductionism: Help or Hindrance in Science and Religion” by Michael Poole teases out the implications of methodological, epistemological and ontological reductionism, showing how the first is essential and the last bumps up against the limits to science. Alister McGrath’s Has science killed God? takes this discussion further with reference to Dawkins, and concludes that:

Dawkins’ atheism seems to be tacked on to his science with intellectual Velcro, lacking the rigorous evidential basis that one might expect from an advocate of the scientific method.

A more recent paper by John Taylor on ‘Science, Religion and Truth’ outlines the realist and relativist accounts of the nature of truth, impacting the understanding of science. This then relates to how objective truth is understood in religious belief and discourse, especially in disagreements in that area.

A fascinating paper on ‘The Age of the Earth’ by Bob White surveys the evidence and concludes hermeneutically. He discusses the scientific basis of geological dating, historical and recent views on the age of the Earth, and some theological implications that follow from the biblical and scientific evidence.

Three papers focused on Genesis are outstanding. Ernest Lucas on “Interpreting Genesis in the 21st century” covers a lot of old ground but expounds both the cultural context and the relevance today very well. Sam (RJ) Berry gives a lucid account of creation and evolution needing to be understood together “to do justice to what we as scientists observe”. Graeme Finlay then looks at “Human Genomics and the Image of God”, showing how we need to understand humans in relation to the genetic story which narrates our biological history, and the personal story concerning cultures, beliefs and behaviour. The genetic account is fascinating, but he doesn’t venture into when and how humans were created in God’s image.

Two historical papers, on Michael Faraday, and the “Galileo Affair”, by Colin Russell and Ernan McMullan respectively, probe the interaction of science and faith in a godly person and in a fraught ecclesiastical situation.

Delving into neuroscience, a paper by Stuart Judge refutes the claim that we are “Nothing but a pack of neurons”. He expounds implications of neuroscience in three positions: strong reductionism, dualism, and dual-aspect monism, which he feels ’has many advantages’. This is followed by Peter Clarke introducing a particular controversy in the area: “The Libet Experiment”.

Rodney Holder’s paper on “Natural Theology” is a later addition to the series and most welcome in framing many of the others. My frequent recourse to Romans 1:20 now has an erudite justification! He quotes Aquinas saying it is presuppositional to articles of faith and revealed theology. It raises questions of cause and of the ordered design of the universe (see Holder’s Design paper above). Obviously, science has often been the basis of applying natural theology – God’s Book of Works, etc, and Holder provides much useful detail for apologetics. He answers some Barthian scepticism on the matter, leaning on Acts 17 and the OT. “Scripture itself asserts that there is a knowledge of God to be obtained from observing nature,” and scientists “may find the best explanation within a theistic framework”.

The papers are available free online in up to 16 languages at https://www.faraday.cam.ac.uk/resources/faraday-papers/

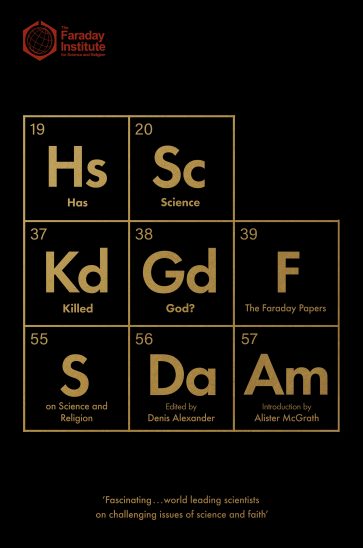

The first 20 Faraday Papers, several updated and revised, were published as a book by SPCK in 2019, with an Introduction by Prof. Alister McGrath. Has Science Killed God? can be ordered from the Faraday Institute for £10.

2