Book reviewed by Kathlyn Ronaldson, January 2025

Circles and the Cross: Cosmos, Consciousness, Christ, and the Human Place in Creation

by Loren Wilkinson

Eugene, Oregon: Cascade Books, 2023; 324 pages

ISBN 9781666746341, first edition, paperback

AU$57.00

Foreword by Peter Harris

Loren Wilkinson is an Emeritus Professor of Regent College, Vancouver. He is a philosopher, an environmentalist, a Christian, is well-read in science, and was one of my teachers when I attended Regent College in the 1980s. This book has been described by one of Wilkinson’s colleagues (Iain Provan) as being about “Life, the Universe, and Everything” which is true, but the subtitle gives a better idea of the depth, reach, and purpose of the book. Wilkinson weaves through this book stories from his own journey, beginning in his childhood on a farm in Oregon, in view of the Cascade Mountains.

The notion of “circles and the cross” is an allusion to many things: one is the Celtic cross with its circle around the place where the pieces of wood intersect, being the location of Christ’s suffering; a second is Andrei Rublev’s icon (1411 or 1425-26) of the Trinity in which the three figures make a circle which the viewer is invited to join.

The book explores three singularities or mysteries: cosmos, consciousness and the cross. Why is there something (cosmos) and not nothing? How is it that humans are conscious, are conscious of consciousness, and are able to reflect on their place in the cosmos? The third mystery is the cross, in which we see the self-giving of the Creator, in death. Bringing these threads together, Wilkinson concludes persuasively, that in the cross there is reason for confidence in the Creator’s sustaining and loving of this world and its creatures despite human destructiveness.

Part I is entitled “Being Conscious in the Cosmos.” The second chapter presents some facts that are reason to wonder about the miracle of the origin of life on earth. One example is the great oxygenation holocaust, in which anaerobic organisms, which had produced oxygen by photosynthesis over a billion years, died or were marginalised by an explosion of aerobic life. In a second example, the resonance level of the carbon nucleus is such that helium and beryllium readily combine to generate an abundance of carbon, the essential basic element of life. Carbon can combine with helium to form oxygen, but this is much less favourable because the resonance of the oxygen nucleus is 0.5% too low, meaning that carbon is not depleted by the formation of oxygen and the balance of carbon and oxygen is favourable to life.

Part II addresses “ Science: Pleasure, Paradox, and Pain.” People are enticed into science by delight at the natural world (senses, right brain) and so investigate to generate factual knowledge (left brain). In this context, Wilkinson points out that the spirit of St Francis of Assisi of loving openness to other creatures led to empiricism, where the scientist stands under creation rather than imposing understanding. Duns Scotus, a Franciscan, is a further significant figure. God is motivated not by reason but acts willingly out of love (voluntarism), each creature has its own distinctiveness (haecceity or this-ness), each creature is “good” in its own right as identified by God in Genesis 1 (univocity of being), and creation is elevated by the incarnation (primacy of Christ).

But as Wilkinson notes Johannes Kepler’s meticulous observations reduced the motions of the planets to geometric terms and Isaac Newton understood the earth and the cosmos as a machine, thus the world was diminished to a supermarket of commodities to be used and manipulated. While the power of scientific understanding improved the human condition, it wounded the planet.

In Part III, “Corrections, Movements and Visions,” philosophical movements, beginning with the Enlightenment, are explored. The Enlightenment reflects a culture in search of certainty, not only in the physical, but also the psychical, to the exclusion of the divine. Romanticism sought to restore the wonder of creation, as exemplified by the English Romantic poets. Coleridge, who was one of these, scorned the reductionism of Newton and Locke, stating in the context of his emerging Christian faith that both consciousness and cosmos must be regarded as mysteries understood “in the light of ‘the eternal act of creation in the infinite I AM’” (p. 145; in Biographia Literaria Vol 1. Reprint, New York: Wiley & Putnam, 1847).

However, relativity and quantum theories indicated that creation could not be understood simply as a machine, but greater complexity, even spontaneity, was present. Further, the precision of parameters underlying the cosmos and life in it, such as that resulting in the balance of carbon and oxygen, mentioned above, suggests purposefulness. Some have therefore adopted a pantheistic world-view in which the universe has an internal purpose. Awareness of environmental connectedness and the growing environmental crisis have led to a search for a new religion, for as Bron Taylor has stated, quoted by Wilkinson, “traditional religions are ill-suited to face this challenge, as they are ‘generally concerned with transcending this world or obtaining divine rescue from it’” (p. 192; in Taylor, Dark Green Religion: Nature Spirituality and the Planetary Future, Berkeley: University of California Press, 2010).

Within Part IV, “Jesus as Surprising News about the Creator,” in a chapter on the Trinity, Wilkinson quotes John Polkinghorne, physicist and theologian, saying in his Gifford lectures in 1993 “The proclamation of the One in Three and the Three in One is not a piece of mystical arithmetic, but a summary of data”(p. 241; in The Faith of a Physicist: Reflections of a Bottom-Up Thinker. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2016). Here Polkinghorne made a connection between the complexity of the deep structure of physical reality and the deep structure of the one God.

In his final chapters, Wilkinson explores most “surprising news about the Creator,” the kenosis (self-emptying) of God, which prompted creation and redemption, both out of love. The very act of creating beings with true self-will means the power of the omnipotent is limited. If we are genuinely free, we must have the ability to follow our own will, not God’s [and, I add to clarify Wilkinson’s meaning, to do so even when not in disobedience]. Without denying the forensic purpose of Jesus’ crucifixion, he suggests, quoting Richard Rohr who cites Duns Scotus, that it was “‘a pure and gracious declaration of the primordial truth’” (p. 264; in “The Franciscan Opinion.” In Stricken by God? Editors: Brad Jersak, Michael Hardin, p. 206-12. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2001). In support of this view, I cite Revelation 13:8 (NIV; 2011), which refers to “the Lamb who was slain from the creation of the world.” Or is it the names that were written in the book of life before the creation of the world (see NIV footnote)? I question whether Christ’s death was necessary without sin, but I can understand the incarnation being intrinsic to the nature of God and his relationship to creation.

With regard to kenosis in creation, Wilkinson quotes Katherine Sonderegger who states “He is content to hold the cosmos in being yet not be an element within it” (p. 269, in Systematic Theology I, Minneapolis, MN: Fortress, 2015), meaning we cannot detect gaps requiring the hypothesis of God, either in the process of evolution or God’s upholding of all things. I add that, similarly, in history and in individual lives, God most often works out his purposes using human agents and natural processes.

Drawing on Gerard Manley Hopkins’ notion of “selving,” that is being oneself (intransitive) or contributing to the selfhood of others (transitive), he notes that our intransitive selving is always costly to others, even without sin, since for example to eat is to consume other creatures. I wonder, therefore, would it have been possible for a population of eight billion humans without sin to thrive without being destructive of this planet? In contrast, God’s selving is always transitive as well as intransitive. We humans can choose transitive selving of other humans and other creatures.

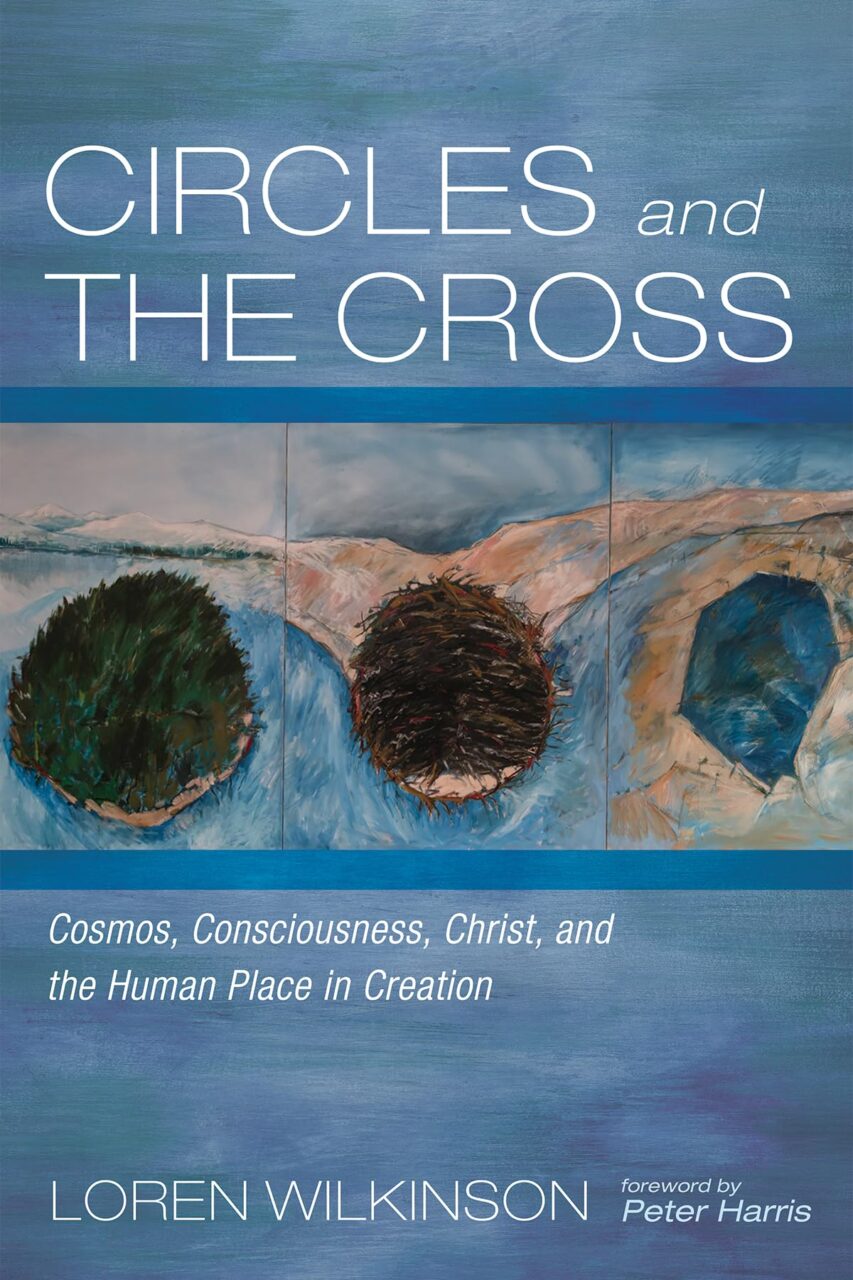

The conclusion describes the triptych, by the Australian Lindsay Farrell, which graces the cover of the book and depicts the central message of the book: that despite our destruction of ecosystems and global warming “creation is ‘safe’ … because the same [as in creating] loving creativity is ever exercised upon it” (p. 273, in W. H. Vanstone, Love’s Endeavour, Love’s Expense: The Response of Being to the Love of God, London: Darton, Longman and Todd, 1977). The left panel of the triptych depicts an island topped by rugged green trees with the snow-capped Cascades in the distance and the skyline of Vancouver just discernible. The centre is of the same island after clear felling, covered by a tangle of tree debris. The right panel is of a lake surrounded by rocks and seen from above. Further inspection reveals outstretched arms across the top of the left and right panels, with the centre panel being of a thorn-crowned head and the right panel an empty tomb with a stone bench.

This is a book born of deep thinking drawing on an extremely broad range of sources. It took me going over the book a second time to catch the trajectory of the book, in terms of the birth of science, the mechanistic understanding of creation, the desire to remove God’s place in our thinking, the intimations of spontaneity in quantum theory and of purpose in the precision of fundamental parameters, the search for religion in the twentieth century, and the centrality of the incarnation, crucifixion, and resurrection of Christ in giving meaning and purpose to the cosmos and each of our lives. The book is easy to read for those with some background in the topics covered, but less easy to comprehend, in the sense of grasping the whole. It is very much worth the effort.