Book Review by Charles Sherlock

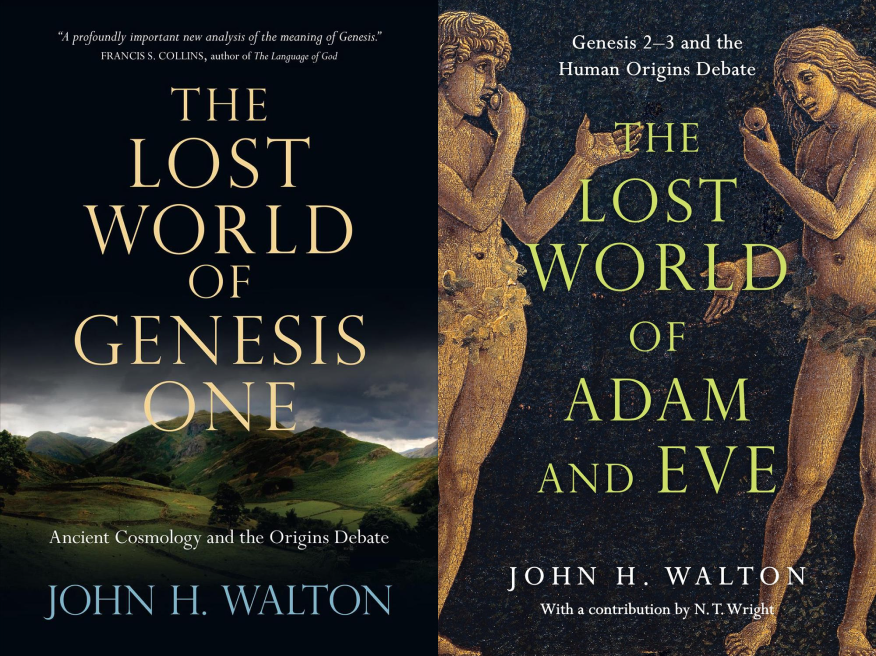

The Lost World of Genesis One: Ancient Cosmology and the Origins Debate

(Downers Grove, IL: IVP Academic, 2009); 192 pages

ISBN 9780830837045, 1st edition, paperback

AUD$25

The Lost World of Adam and Eve: Genesis 2–3 and the Human Origins Debate

(Downers Grove, IL: IVP Academic, 2015); 258 pages

ISBN: 9780830824618, 1st edition, paperback

AUD$37

It is so good to read an original book, one that goes back to origins. Both members of this closely related pair are exemplary here. Walton not only delights in the Christian Scriptures in their original languages, but also the contexts in which they were set. Hebrew terms are analysed thoroughly in ways accessible to all readers, and full citations made of a raft of ancient Babylonian and similar texts. All are treated with respect and care.

John H. Walton teaches Old Testament at Wheaton College, Illinois—a bastion of intelligent US evangelical thought. His target audience is Christians for whom “science” raises issues around the origins of the universe, and human beings in particular. These issues are addressed, and fully, but always with biblical authority front and centre. Decades of engaging with students for whom these things matter lie behind the writing.

Each book is arranged as a series of Propositions—rather like scholastic method but much more accessibly. Two examples are “Proposition 7: Divine Rest is in a Temple” from the first book, and “Proposition 20: It Is Not Essential That All People Descended from Adam and Eve” from the second. The approach sounds awkward, but it works: the writing is clear, and consistently directed to the topic in hand.

A consistent theme is that what the Bible teaches must be understood against the culture of the writers involved. Walton is scrupulous in citing ancient texts fairly, to illuminate rather than control Old Testament passages. A notable feature is the significance of “sacred space” and the place of “temples” in human life in the Genesis texts considered.

The Lost World of Genesis One has 18 Propositions, roughly alternating between outlining ancient cosmologies and how these assist in understanding Genesis 1. That God is the Creator of all is affirmed strongly but it is concluded that the text says very little about modern historical and scientific concerns. This does not mean that Genesis says nothing to us, however! Walton’s calmly inspiring exegesis encourages a whole-hearted response to God’s work in and purposes for creation—and new creation.

Summarising Walton’s conclusions might stop you reading his book! His overall argument—to my mind, a convincing one—is that Genesis 1 describes God creating functions from “non-order” in terms that matter to humans: time, weather, food, and space, then functionaries that order these. The climax is God taking up his presence in the cosmos as “temple,” resting from work in order to rule (what does this mean for the Sabbath?).

The Lost World of Adam and Eve opens with five Propositions that summarise issues of hermeneutics covered in the earlier book. From then on, however, we are taken on a lively, intriguing, and refreshing engagement with Genesis 1 and 2. Did you realise that “other half” is a better translation than “rib” for Eve? Had you ever thought of Adam and Eve as “priests in sacred space”? Walton makes no reference to feminism, but his exegesis raises helpful insights into gender issues as well as scientific concerns.

A brilliant discussion of “sin” in Genesis 2–3 in Propositions 15–18 is the second book’s highlight, with a magnificent discussion of how Paul takes this up in Romans 5 and 1 Corinthians 15 (aided by N. T. Wright, though not as readably!). Walton engages effectively with the Western theological tradition on the “image of God” and (origin-al) sin from Augustine on. He argues that this unhelpfully over-emphasises what we are saved from, rather than the vocation to which we, and creation as a whole, are called.

The final Propositions in both books turn from the biblical text to address specific issues raised by modern sciences—”big bang,” evolution, genetics, and the like. The focal question is consistently “What precisely does the Bible affirm about these?” The temptation for Christians who are scientists to skip to these chapters must be resisted: the books as a whole shed light on research method and conclusions, which matter far more for science.

I wish I had read these books when I began teaching theology 50 years ago. As it happens, my approach to the doctrines of creation and theological anthropology run along similar lines to Walton, but not nearly as creatively.

This pair of books should be texts in every introductory Old Testament course, in every church library—and read by scientists for whom Christian faith raises problems. I have no hesitation in commending them warmly.