Review of Evolution and the Fall, edited by William T. Cavanaugh and James K. A. Smith.

“This book addresses a set of problems that arise from the encounter of traditional biblical views of human origins with contemporary scientific theories about the origin of the human species.”

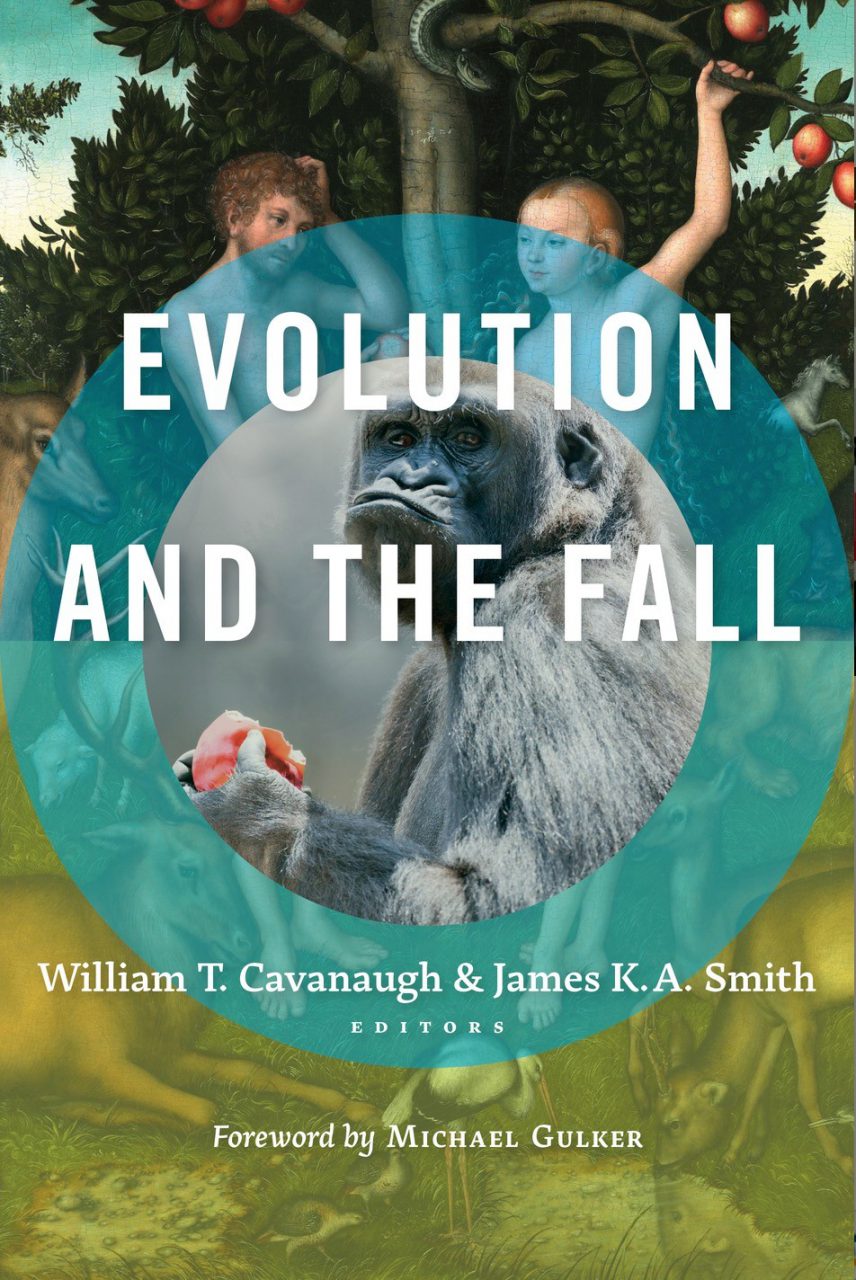

So begins the introduction of Evolution and the Fall edited by William T. Cavanaugh and James K. A. Smith. Cavanaugh is a professor of Catholic Studies while Smith is a professor of philosophy. The fact that this book is edited by two non-scientists, in hindsight, probably should have made me anticipate that this book would not be easy reading for someone from a scientific background, and the fact that it was is a bit of a shame, since the issues they wish to discuss are of equal importance to scientists as well as to theologians and philosophers.

To be fair, there several chapters that were written with a broader audience in mind and helped to expand my thinking on this subject. Others, on the other hand, were hard to penetrate and were seemingly written with the authors’ peers in mind.

The science, however, is faithfully laid out up front in a chapter by Darrel L. Falk (emeritus professor of biology and former BioLogos president) which I found to be especially lucid, spelling out the experimental evidence and rationale for present-day theories and dispelling common misconceptions about evolution.

Other highlights include the chapter by Smith (a philosopher) on “What Stands on the Fall,” the chapter by J. Richard Middleton (professor of biblical worldview and exegesis) on “Reading Genesis 3 Attentive to Human Evolution” and the chapter by ISCAST fellow Peter Harrison, “Is Science-Religion Conflict Always a Bad Thing?” that concludes the book.

Another criticism I would have of this book is the range of topics it tries to cover, touching on topics as diverse as early-modern political theory and transhumanism. While I found reading about such topics interesting, they would not be on my short list (as a scientist) of critical issues to discuss in this area, and I felt more space could have been devoted to such central issues. Writing on the important issue of the historicity of Adam, for example, Aaron Riches (a theologian) does not seem to think it worth offering a “systematic nor comprehensive account of the debate or its solution” preferring instead to “merely [offer] a provocation in favour of a mystery.”

So I came away from this book having encountered unexpected and interesting ideas that have expanded my perspective on the discourse on evolution and the fall, while at the same time a bit disappointed not to have had my itch satisfactorily scratched in this area.