Christian Perspectives on Science and Technology, New Series, Vol. 4 (2025), 125–144

Abstract: This essay contributes to a transversal dialogue between science and theology. While considering natural processes, it interprets nature through the lens of God’s self-revelation in Christ and Scripture. More precisely, focusing on photosynthesis, specifically Photosystem II, I argue that the system’s fine-tuned properties, which enable oxygen production essential for multicellular life, resonate strongly with Christian theism. Moreover, Photosystem II’s self-sacrificial function reflects a kenotic pattern embedded in creation, echoing the self-giving nature of the Triune God. While not seeking to prove the Trinity, or God’s existence for that matter, this study shows how scientific insights can illuminate theological themes, deepening understanding and enriching the vocation of Christians engaged in science.

Alister McGrath has advocated an approach to natural theology whereby science is examined through a theological lens. His proposal anticipates what recently came to be called science-engaged theology.[1] This method does not seek to prove the existence of God from nature; rather, it employs Christian theology as an interpretative framework for observing the natural world as described by modern science.[2] This approach reads nature with an awareness of God’s hiddenness, yet anticipates that creation may, to some extent “echo its origin and goal.”[3] Using this approach, I explore a key component of photosynthesis: Photosystem II (hereafter, PS II). This analysis considers how, when perceived through a theological lens, PS II appears to bear vestiges of the Triune God.

Photosynthesis, meaning “synthesis with light,” is the biological process through which light energy is captured and converted into biochemical energy needed for life on Earth. This process provides all our food and most of our energy resources through fossil fuels.[4] Importantly, photosynthesis also produces oxygen (O2). Over geological eras, this process transformed Earth’s atmosphere by increasing oxygen levels, enabling multicellular life to exist.[5] This foundational role in sustaining life makes photosynthesis a compelling subject for theological reflection.

Scientific investigation into PS II over the last fifty years has revealed two striking features. First, PS II exhibits remarkable fine-tuning at a sub-nanometre scale: each atom is precisely positioned. Second, despite this exquisite design, PS II is irreversibly damaged in the very act of splitting water, requiring continual replacement. In other words, its life-sustaining function depends on its own destruction—a paradox that invites theological reflection on patterns of self-giving within creation.

This essay proceeds in four stages. First, it outlines the scientific understanding of photosynthesis and PS II. Second, it develops a theological argument that self-giving kenosis constitutes the life of the triune God and explores its implications for a doctrine of creation. Third, it applies this theological lens to interpret photosynthesis. Finally, it offers personal reflection on how the dialogue between science and theology enriches both perspectives.

Photosynthesis and Photosystem II

In the published version of his Gifford Lectures, McGrath briefly discusses the biochemistry of photosynthesis, outlining its overall process and its role in oxygen production.[6] He argues that while the fine-tuning evident in biological catalysts, such as Photosystem II, can arise through the evolutionary process of natural selection, it is important to recognise that the functional properties of the catalysts are dependent on the predetermined properties of chemical elements, such as manganese, used within these biological systems.[7] This paper examines PS II in more detail and pays particular attention to the damage that occurs to PS II through the water splitting process.

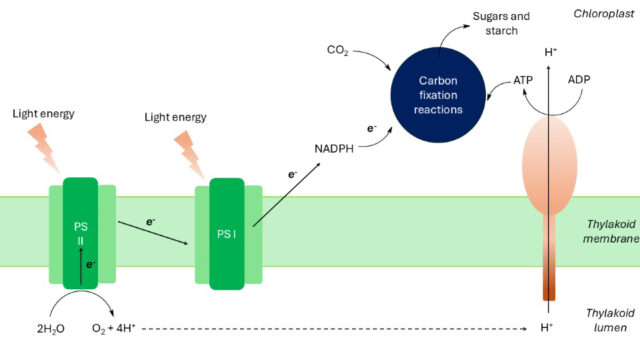

Oxygenic photosynthesis is an intricate process involving multiple enzymes, as summarised in Figure 1, whereby light energy is converted into chemicals such as starch and sugar. Photosystem II and Photosystem I work in tandem to carry out oxygenic photosynthesis.[8] PS II initiates this process by catalysing the splitting of water molecules to provide electrons that drive the entire oxygenic photosynthetic process. Water splitting also produces molecular oxygen (O2), and hydrogen ions (H+). The latter contribute to generating adenosine triphosphate (ATP), the chemical energy that powers carbon fixation, converting carbon dioxide into sugars and starches, key building blocks for biological life.[9]

The importance of the second product of water splitting, O2, cannot be overstated. For most of Earth’s history, the atmosphere contained virtually no O2, supporting only anaerobic bacteria. The emergence of cyanobacteria capable of oxygenic photosynthesis initiated a dramatic rise in atmospheric oxygen, enabling the evolution of multicellular organisms and the extraordinary biodiversity we observe today.[10] This central role in sustaining and transforming life underscores why photosynthesis, and PS II in particular, offers fertile ground for examination through a theological lens.

Figure 1: A summary of the processes involved in photosynthesis. Note the role of PS II in splitting water and providing electrons (e–) to the downstream processes.

The Chemistry of PS II

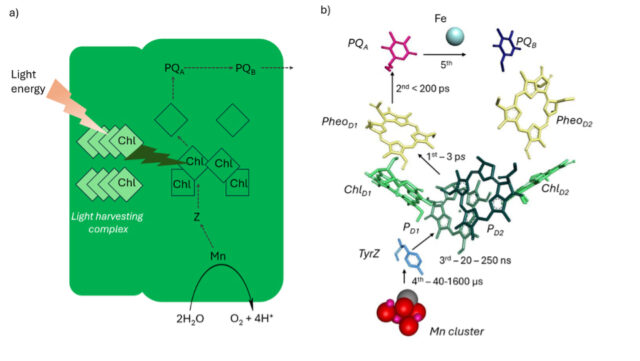

Over the last forty years, advances in protein crystallography have given us remarkable insights into the complexity of PS II. This technique allows scientists to determine the exact atomic-level structure of a protein.[11] PS II has a highly intricate molecular architecture enabling it to absorb light energy and transfer it as electrons and protons (H+) to other components of the photosynthetic machinery. PS II is a large protein assembly that contains hundreds of pigments such as chlorophylls. These pigments are excited by light energy and transfer this energy to the reaction centre (see Figure 2a).

Within the reaction centre are two chlorophyll pigments that are positioned close enough to each other to share bonding orbitals and react as a single compound when excited (PD1 and PD2; see Figure 2b). Excitation of this special chlorophyll pair initiates charge separation, followed by the transfer of electrons down an electron transport chain.[12] Key to the whole system is that the flow of electrons occurs only in one direction. This unidirectional flow is essential for creating the conditions necessary for the challenging chemistry of splitting water, which takes place at the manganese cluster.

Following excitation in the reaction centre of PS II, there is very fast electron transfer from chlorophyll (Chl) to pheophytin (Pheo) within 3 picoseconds (3 x 10-12 seconds; see Figure 2b, Step 1). The second electron transfer is slightly slower, occurring in under 200 picoseconds (see Figure 2a, Step 2).[13] These ultrafast steps prevent energy loss as heat and ensure efficient electron flow. Not only is this electron transfer very fast, it is also thermodynamically fine-tuned to ensure that the electrons flow in the correct direction and not in reverse. The combination of fast kinetics and favourable thermodynamics means that this electron transfer is “virtually irreversible and highly efficient.”[14]

Figure 2 a) A simplified diagram of PS II. Broken arrows indicate the pathway of the electron transfer chain. b) Shows the atomic level detail of the reaction centre of PS II. An electron is released when excited by light energy. The order and timescale of the electron transfer steps is shown. Abbreviations: Chl = chlorophyll; Pheo = pheophytin; PQ = plastoquinone; TyrZ = tyrosine Z; Mn = manganese cluster; ps = picosecond; ns = nanosecond; µs = microsecond.

Following charge separation, an electron hole in P680 is filled by an electron from a tyrosine residue (TyrZ). This process occurs a thousand times slower than the first two steps (20 to 250 nanoseconds). The slower third electron prevents reverse reactions, such as the reduction of O₂ back to water.[15] The authors of Lehninger Principles of Biochemistry explain this remarkable example of fine-tuning, saying: “Nothing is left to chance collision or random diffusion.”[16]

This precisely controlled sequence of electron transfer steps ultimately removes an electron from the manganese cluster, known as the Oxygen Evolving Complex (OEC) (see Figure 2b, Step 4) transforming it into an oxidising agent capable of splitting water. However, four electrons need to be removed from the cluster for water splitting to occur. These electrons are transferred one at a time to a nearby tyrosine residue (see Figure 2b, TyrZ), with each transfer requiring the sequential absorption of a photon.[17] As two water molecules are oxidised, four electrons are provided into the photosynthetic pathway and one molecule of O2 is produced.

While scientific techniques such as Electron Paramagnetic Resonance (EPR) spectroscopy and quantum chemical calculations have provided insights into how the OEC carries out water splitting, there are still many aspects that are not fully understood.[18] Indeed, the more we uncover about PS II, the more its elegance and complexity invite reflection, not only on its biochemical sophistication but also on the deeper patterns it may reveal about the nature of creation.

Photodamage in PS II

In addition to an appreciation for the elegance and complexity of PS II, science has also discovered a “lingering enigma” in this system: it is irreversibly damaged during the very process of photosynthesis.[19] Under normal light conditions, PS II has a functional lifetime of as little as 30 minutes.[20] This light-induced damage, termed photodamage, is a complex phenomenon that is not fully understood.[21] The main function of PS II is splitting water to produce O2. This unavoidably occurs near photoexcited chlorophyll molecules. When O2 interacts with these excited chlorophyll molecules it forms singlet oxygen, a highly reactive species that initiates damage to the protein structure and the chlorophyll pigments within it.[22] In other words, PS II is destroyed by performing its essential function. To sustain photosynthesis, damaged components must continually be replaced, a process that consumes significant chemical energy in the form of ATP, the key product of photosynthesis (see Figure 1).[23]

This energetic cost explains why deciduous trees suspend photosynthesis in winter, as the chemical energy that can be gained through photosynthesis is less than that required to replace PS II. When chlorophyll production stops and damaged PS II is not repaired, other pigments such as carotenoids (yellow and orange) and anthocyanins (red and purple) become visible, producing the vibrant colours of autumn. Hayley Bennett poetically observes that the plants “shed the green veils they have been hiding under, to take on an ensemble of red, yellow and orange.”[24] This paradox, that multicellular life is sustained through a process that entails continual self-destruction, offers a profound point of contact for theological reflection on the self-giving character of creation.

Moving from Scientific Observation to Theological Interpretation

Summarising what has been discussed thus far, photosynthesis and PS II have been intensively studied. PS II splits water to provide the source of electrons for photosynthesis. PS II is both remarkably tuned to carry out this difficult chemical reaction but also irreversibly photodamaged through this process. As a result, PS II has a short lifetime under operating conditions and needs to be continually repaired.[25]

At this point, we must pause to consider the limits of what we can gain from the scientific study of photosynthesis and PS II. While scientific study can provide us with precise and useful data and information about how a process works, it is unable to answer deeper or metaphysical questions.[26] Addressing these questions belongs to the realms of philosophy and theology. It is for this purpose that I seek to examine the scientific findings about PS II through a theological lens. The goal of this approach is to find out the extent to which scientific discoveries can inform theology—after the fashion of science-engaged theology—and to test whether trinitarian theology can provide “an extended context within which to accommodate certain striking features of our current understanding” of creation as viewed by science.[27]

Defining the Theological Lens

As discussed above, rather than seeking to prove the existence of God from nature, McGrath’s approach uses what we know of God through revelation in Scripture as a lens to view nature and scientific discoveries.[28] Following McGrath’s approach, I will be examining PS II as part of the creation by a triune God, paying particular attention to the concept of “vestiges of the Trinity.”[29] With this in mind, we next need to define the theological lens to be used in order to argue that aspects of creation mirror relationships within the Trinity.

Trinitarian Kenosis

Christian tradition affirms one God in three persons (Father, Son, and Spirit) who share an undivided essence (see 1 Corinthians 8:6). Each person of the Trinity possesses the fullness of the divine essence yet is distinguished by relational identity[30]—or uniqueness in terms of relating with the other two persons. The term perichoresis, first used by Gregory of Nyssa,[31] describes this dynamic relationship. Perichoresis literally means rotation and suggests the image of a “divine dance.”[32] Although the term perichoresis is not used in the Bible, there are many descriptions of the dynamic relationship between the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, such as mutual praise and thanksgiving,[33] intimate knowing,[34] mutual indwelling,[35] mutual love expressed through both speech[36] and actions.[37] In seeking to capture the “dance-steps” of perichoresis, Jaqueline Service has proposed the concept of kenotic-enrichment.[38]

The concept of kenosis, meaning “to be emptied,” derives from Philippians 2:7, which describes Christ as “emptying himself” (heauton ekenosen). In post-Reformation theology, kenosis became central to Christological debates, particularly in the 19th century. In response to historical-critical challenges to the divinity of Christ, Protestant theologians proposed that Jesus voluntarily suspended certain divine attributes during the incarnation.[39] This “kenotic Christology” sought to reconcile the humanity of Jesus with scriptural and traditional assertions of divinity.[40] While these discussions were often framed in terms of limitation or self-renunciation, they laid the groundwork for a deeper theological exploration of divine self-giving.

In the 20th century, theologians such as Karl Barth, Wolfhart Pannenberg, Hans Urs von Balthasar, and Jürgen Moltmann reframed kenosis as being intrinsic to the eternal life of God, rather than a temporary act in the incarnation. Scripture offers glimpses of this self-giving dynamic: the Son handing the kingdom back to the Father (1 Corinthians 15:24), the Son “gifting” his life in unwavering trust (Luke 23:46), and the gifted sustenance of the Spirit in the resurrection (Romans 8:11). The prayers of Jesus in John 17 reveal mutual gifting of glory within the Trinity.[41]

Perceptively, David Bentley Hart highlights the relational interactions described at the baptism of Jesus as revealing “God whose life of reciprocal giving away and containing is also a kind of dancing and the God who is delighting in the dance.”[42] Von Balthasar contends that mutual self-giving constitutes the life of the triune God.[43]

Against this backdrop, Moltmann explains that Christ’s kenosis in Philippians 2:7 is not a denial or self-renunciation of divinity but is in fact the revelation of it.[44] Service expresses a similar perspective, pointing out that “the inherent nature of kenosis, vividly expressed in Christ, originates in the being of the triune God.”[45] She argues that the glory of the Trinity is both demonstrated and achieved through divine self-giving (John 13:31). Importantly, Service shows that divine kenosis is not depleting but is enriching.[46]

Kenosis and Creation: A Spectrum of Views

Creation can be viewed as an act of kenosis by the triune God. Interpreting creation as a kenotic act of God is central to the approach that I take in this essay. However, scholars differ on how far divine kenosis extends in creation. Process theologians such as Ian Barbour argue that kenosis in creation involves voluntary self-limitation of God’s power, which results in granting creation genuine freedom and exonerating God of responsibility for evil and suffering.[47] John Polkinghorne, in turn, conceives kenosis as the “risk” God takes by submitting to “the free process of creation.” He goes so far as to say that “the Creator’s kenotic love includes allowing divine special providence to act as a cause among causes.”[48] Moltmann goes further, describing creation as an act of divine contraction: God withdraws to make room for creation.

Each interpretation carries significant metaphysical and moral implications.[49] For example Barbour’s position of divine self-limitation reduces God’s omnipotence and omniscience while Moltmann’s view of kenosis leads to God and creation becoming mutually dependent.[50] The traditional doctrine of creation as espoused, for example, by the Nicene Creed, does not make God dependent on creation and maintains ontological distinction between God and creation. [51] Webster explains how God is complete and independent of creation saying “no perfection of God would be lost, no triune bliss compromised were the world not to exist, no enhancement of God is achieved by the world’s existence.”[52] This essay views creation as a kenotic action of the triune God but seeks to avoid making God dependent on creation or conflating creation and the Creator.

Vestiges of the Trinity in Creation

Theologians such as Augustine, Bonaventure, and Jonathan Edwards examined the natural world expecting it to bear signs of God, in particular signs of the trinitarian relations envisioned in Scripture.[53] Importantly, these traces, imprints, signs, or vestiges do not prove the Trinity; rather, they are “profoundly consonant with a theology of nature that sees the relation of perichoretic exchange between the divine Persons as lying at the heart of the Source of all created reality.”[54] If kenosis amounts to perichoretic “dance-steps” within the Trinity, then creation itself may bear traces of this self-giving pattern. Moving forward, I will look for such vestiges or patterns within PS II.

Examining Photosynthesis through a Theological Lens

Provision

Through photosynthesis, light energy is used to fix carbon dioxide producing food, the chemicals that make up wood and other plant materials, providing shelter for animals and fuel for warmth. Fossilised plant material remains a major energy source today, all ultimately derived from photosynthetic organisms’ ability to transform gaseous carbon dioxide into other carbon-based chemicals. Photosynthesis also gives us oxygen. Without cyanobacteria, Earth’s atmosphere would have remained anoxic, supporting only anaerobic bacteria. The rise of oxygen enabled the emergence of complex life and the extraordinary biodiversity we see today. Photosynthesis by plants and algae continue to make the oxygen we breathe today. When viewed through a theological lens, photosynthesis appears as the means by which God provides for creation, including the oxygen within the biosphere of Earth.

Fine-Tuning and Purpose

PS II, the enzyme that initiates photosynthesis, is astonishingly fine-tuned. Protein crystallography and spectroscopy reveal atomic-level precision far beyond the reach of any microscope. This observation is valid for many other enzymes within biology. When PS II is considered theologically, as a creation of the triune God, such fine-tuning, intricacy, and complexity are neither surprising nor unexpected. God creates with purpose, not on a whim; therefore, we should expect to find highly and precisely tuned systems within creation.[55] This level of fine-tuning or order is “rooted in and consistent with the life of the triune God.”[56] Hart explains that “creation is not the overflow of some ungovernable perturbation of the divine substance, or a tenebrous collusion of ideal form and chaotic matter, but purely an expression of the superabundant joy and agape of the Trinity.”[57]

It is important to recognise that other interpretative lenses could be used to examine PS II, leading to different conclusions.[58] One commonly used lens is evolutionary naturalism, which seeks to explain fine-tuning without invoking a divine origin. McGrath notes that although fine-tuning can result from the evolutionary process, evolution’s ability to fine-tune itself depends on predetermined properties of chemical elements within their catalytical states. It is the quantum mechanical properties of metals that have enabled evolution to develop solutions such as photosynthesis and enzymes such as PS II.[59] Critically, the existence of fine-tuning noted within PS II does not prove the existence of a deity. However, when contemplated through a theological lens, fine-tuning is deeply resonant with PS II being part of creation by a triune God who operates at the heart of all created reality.[60]

Kenotic Patterning

Alongside the intricate fine-tuning of PS II lies a paradox: PS II is irreversibly damaged in performing its essential function. Polkinghorne argues that trinitarian theology provides “an extended context within which to accommodate certain striking features of our current understanding” of creation viewed by science.[61] I therefore propose that viewing PS II as part of creation by a triune God occasions a deeper theological insight into photodamage. Thus, viewed through a trinitarian lens, PS II is not only life-giving but self-giving; it sustains life through its own destruction. This pattern resonates with the kenotic life of the Trinity, where self-giving is pivotal for perichoretic life. The photodamage of PS II can thus be theologically interpreted as a mark of the nature of the triune Creator within creation or a vestige of the Trinity. This interpretation stands in contrast with evolutionary naturalism, where photodamage is seen as a limitation “for which nature has not found a perfect solution to circumvent.”[62]

While the focus of this essay is on kenotic patterning within PS II, similar patterns have been identified elsewhere in biology. A good example is the continuous recycling of nutrients through the carbon and nitrogen cycles. Kenotic patterns extend beyond biology to astrophysics, for example, where a star must “die” to provide the elements for new stars.[63] Poignantly, Rolston notes kenotic patterns within predation, saying

Since the beginning, the myriad creatures have been giving up their lives as a ransom for many … The secret of life is seen now to lie not so much in the heredity molecules, not so much in natural selection and the survival of the fittest … The secret of life is that it is a passion play.[64]

Such widespread kenotic patterning within creation should be expected precisely because it emanates from the Triune God and bears trinitarian marks. The photodamage observed in PS II exemplifies such a pattern, not as evidence of pantheism, but as a sign of the relational link between the Triune God and creation. As Jacqueline Service notes:

The pattern of God’s being is, not surprisingly, the deep patterning for human life and the created order—entered into and actualized with increasing glory by worship that recognizes and orientates to the divine ways.[65]

How Science and Theology Can Enrich Each Other

This essay began with a desire to contribute meaningfully to the dialogue between science and theology, aiming to enrich both disciplines. It is the result of a longterm effort to integrate my work as a scientist, in the area of biological chemistry, and my Christian faith. As I conclude, I reflect on how this journey has deepened my understanding of both creation and Creator.

Robert Boyle, often regarded as the father of modern chemistry, eloquently stated:

The book of nature is a fine and large piece of tapestry rolled up, which we are not able to see all at once, but must be content to wait for the discovery of its beauty, and symmetry, little by little, as it gradually comes to be more and more unfolded, or displayed.[66]

Boyle saw himself as a priest of nature, believing that his scientific pursuits were not hindered by faith but inspired by it. He viewed science as a form of worship serving “the chiefest temple of God.”[67] This perspective resonates deeply with me. It encourages a posture of reverence and curiosity, one that seeks not merely to publish or secure funding, but to uncover the intricacies of creation. This frame of mind I advocate makes me a far better scientist.

Studying PS II through a theological lens has prompted moments of awe and reflection. These moments invite not only scientific admiration but theological contemplation. It is in these moments that I pause, marvel, and worship. As theologian David Bentley Hart suggests, the feelings of awe and wonder when encountering beauty—whether in the grandeur of autumn leaves or the submicroscopic elegance of PS II—are ultimately an experience of love, leading us back to the “inexhaustible wellspring of love.”[68]

This integrative process has also challenged and refined my theological understanding. In exploring the kenotic patterning within PS II, I initially saw these as divine fingerprints, traces of the Creator on the clay of creation. However, revisiting the doctrine of creation reminded me that such metaphors risk reducing God to a mere craftsman.[69]

An alternative metaphor to explain the origin of these vestiges was proposed by Sergiĭ Bulgakov, who posits that, given that apart from God there is nothing, God created “out of his essence.”[70] He employs a botanical metaphor, describing the process as “implanting divine seeds.” While on face value this may appear to lead to pantheism or panentheism, Bulgakov carefully maintains an ontological distinction between God and creation. He describes the divine seeds as “initial, incomplete and nondefinite,” explaining that the “seed is only a seed, not the plant.”[71] Crucially, he emphasises that “the boundary between the Creator and creation must be preserved unconditionally, but the existence of this boundary does not abolish the relation or link between God and the world.”[72] This metaphor however still risks conflating God with creation.

I propose maybe a better metaphor is to think of these vestiges as expressions of what I call divine DNA, not the whole of God, but informational patterns that actively shape and sustain creation. In modern molecular biology we move genes around amongst different organisms; this does not change the ontology of the organism. More importantly, DNA remains active, dynamic, and formative in contrast to a seed that disappears as the plant grows. To me, this metaphor better captures the ongoing relationship between Creator and creation: the created world is distinct yet intimately connected, wholly dependent on God.

This journey has also illuminated the tension between God’s transcendence and immanence. Western theology often emphasises the transcendence of God as wholly other, sovereign, and beyond. Yet this emphasis can obscure the biblical witness to God’s nearness: “in whom we live and move and have our being” (Acts 17:28). Through this study, I’ve been challenged to hold both truths together. The God who created PS II is not distant but present—active in sustaining life, revealing beauty, and inviting us into deeper communion.

In the end, the scientific investigation of PS II has not only expanded my understanding of photosynthesis, but has also drawn me into richer theological reflection. It has reminded me that creation is not God, but it is God’s, saturated with divine presence, purpose, and love. And in studying it, I find myself drawn closer to the One who made it.

Conclusions

The process of examining Photosystem II (PS II) through a theological lens invites us to pause and marvel at the extraordinary complexity and fine-tuning embedded within this molecular system. PS II is not merely a chemical mechanism, it is a window into the deeper mystery of creation, revealing patterns of order, beauty, and purpose that resonate with theological themes.

This exploration has led us into the heart of trinitarian theology, where the kenotic love shared within the Trinity overflows into creation itself. The self-giving nature of God, expressed in the relational dynamics of Father, Son, and Spirit, finds echoes in the sacrificial and sustaining patterns observed in PS II. Such reflections deepen our understanding of divine immanence: God is not only the transcendent Creator but also intimately present in the processes that sustain life.

Perhaps the best way to conclude this essay is to reflect on the words of a 12th-century monk, Bonaventure, who wrote with a feeling of awe at nature:

The creation of the world is a kind of a book in which the Trinity shines forth, is represented and found as the fabricator of the universe … Hence, as if by certain steplike levels, the human intellect is born to ascend by gradation to the supreme principle, which is God.[73]

Acknowledgments I am deeply grateful to the many people who have helped, encouraged, and supported me throughout this journey. In particular, I thank Ross McKenzie for his guidance and for exemplifying what it means to integrate work and faith as a Christian. I am also indebted to Sara Rapson for her insightful discussions and meticulous reading of multiple drafts of this paper. Finally, I wish to thank Jacqueline Service for introducing me to the concept of kenosis and inspiring my interest in trinitarian theology.

Disclaimer The views expressed in this essay are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of any affiliated organisation.

The author reports there are no competing interests to declare.

Received: 18/09/25 Accepted: 30/11/25 Published: 16/02/26

[1] See, for example, John Perry and Joanna Leidenhag, Science-Engaged Theology, Cambridge Elements: Elements of Christianity and Science (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2023) and “What Is Science-Engaged Theology?” Modern Theology 37, no. 2 (2021): 245–253.

[2] Alister E. McGrath, The Open Secret: A New Vision for Natural Theology (Malden: Blackwell, 2008), 3.

[3] Alister McGrath, A Fine-Tuned Universe: The Quest for God in Science and Theology, Gifford Lectures 2009 (Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press, 2009), 69.

[4] Robert E. Blankenship, Molecular Mechanisms of Photosynthesis (Oxford: Blackwell Science, 2002), 1.

[5] Blankenship, Molecular Mechanisms, 2.

[6] McGrath, A Fine-Tuned Universe, 158–159.

[7] McGrath, A Fine-Tuned Universe, 164.

[8] Blankenship, Molecular Mechanisms, 9-10.

[9] Blankenship, Molecular Mechanisms, 6.

[10] Woodward W. Fischer et al., “Evolution of Oxygenic Photosynthesis,” Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences 44 (2016): 647.

[11] Wolfgang Lubitz et al., “Water Oxidation in Photosystem II,” Photosynthesis Research 142 (2019): 105.

[12] Roberta Croce and Herbert van Amerongen, “Natural Strategies for Photosynthetic Light Harvesting,” Nature Chemical Biology 10 (2014): 492.

[13] Lubitz et al., “Water Oxidation,” 109.

[14] David L. Nelson et al., Lehninger Principles of Biochemistry, 5th edn (New York: W. H. Freeman & Company, 2008), 752.

[15] Lubitz et al., “Water Oxidation,” 109.

[16] Nelson et al., Lehninger Principles of Biochemistry, 752.

[17] David L. Nelson et al., Lehninger Principles of Biochemistry, 8th edn (New York: W. H. Freeman & Company, 2021), 714.

[18] Lubitz et al., “Water Oxidation,” 106.

[19] Marvin Edelman and Autar K. Mattoo, “D1-Protein Dynamics in Photosystem II: The Lingering Enigma,” Photosynthesis Research 98 (October 2008): 609.

[20] Lubitz et al., “Water Oxidation,” 109.

[21] Imre Vass, “Molecular Mechanisms of Photodamage in the Photosystem II Complex,” Biochimica et Biophysica Acta—Bioenergetics 1817 (January 2012): 209.

[22] Lubitz et al., “Water Oxidation,” 109.

[23] Nixon et al., “Recent Advances in Understanding the Assembly and Repair of Photosystem II,” Annals of Botany 106 (2010): 12.

[24] Hayley Bennett, “Trees Show Their True Colours in Autumn,” Royal Society of Chemistry, 12 October 2023, https://edu.rsc.org/everyday-chemistry/the-chemistry-behind-leaves-changing-colour-and-falling-from-trees/4018155.article (accessed 10 December 2025).

[25] Lubitz et al., “Water Oxidation,” 109.

[26] “Text 4: Karl Barth, Church Dogmatics,” in T&T Clark Reader in Theological Anthropology, ed. M. A. Cortez and M. P. Jensen (New York: Bloomsbury T&T Clark, 2017), 37–38.

[27] John Polkinghorne, Science and the Trinity: The Christian Encounter with Reality (London: SPCK, 2004), 62.

[28] Alister E. McGrath, A Scientific Theology, vol. 1 (Edinburgh: T&T Clark, 2001), 294.

[29] Nicola Hoggard-Creegan, “Vestiges of Trinity,” in Trinitarian Theology after Barth, ed. Myk Habets and Phillip Tolliday (Cambridge: The Lutterworth Press, 2011), 201.

[30] John Webster, “Trinity and Creation,” International Journal of Systematic Theology 12, no. 1 (2010): 9, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2400.2009.00489.x.

[31] Daniel F. Stramara, Jr, “Gregory of Nyssa’s Terminology for Trinitarian Perichoresis,” Vigiliae Christianae 52, no. 3 (1998): 257.

[32] Paul S. Fiddes, Participating in God: A Pastoral Doctrine of the Trinity (Westminster: John Knox Press, 2001).

[33] Matthew 11:25; John 11:41.

[34] Romans 8:26–27; Matthew 11:27; John 10:15.

[35] John 14:10–11.

[36] Mark 1:11; Matthew 17:5.

[37] Isaiah 11:2; Acts 10:38.

[38] Jacqueline Service, Triune Well-Being: The Kenotic-Enrichment of the Eternal Trinity (Lanham, MD: Lexington Books), 141.

[39] Christoph Schwöbel, “The Generosity of the Triune God and the Humility of the Son,” in Kenosis: The Self-Emptying of Christ in Scripture and Theology, ed. Paul T. Nimmo and Keith L. Johnson (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2022), 298.

[40] Schwöbel, “The Generosity of the Triune God,” 299.

[41] Service, Triune Well-Being, xiv.

[42] David Bentley Hart, The Beauty of the Infinite: The Aesthetics of Christian Truth (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2004), 175.

[43] Hans Urs von Balthasar, The von Balthasar Reader, ed. Medard Kehl and Werner Loser, trans by Robert Daly and Fred Lawrence (New York: Crossroad Publishing Company, 1997), 428–429.

[44] Jürgen Moltmann, “God’s Kenosis in the Creation and Consummation of the World,” in The Work of Love: Creation as Kenosis, ed. John C. Polkinghorne (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2001), 140.

[45] Service, Triune Well-Being, xviii.

[46] Service, Triune Well-Being, 143.

[47] Ian G. Barbour, “God’s Power: A Process View,” in The Work of Love: Creation as Kenosis, ed. J. C. Polkinghorne (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2001), 5.

[48] J. C. Polkinghorne, “Kenotic Creation and Divine Action,” in The Work of Love: Creation as Kenosis, ed. J. C. Polkinghorne (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2001), 104.

[49] Sarah Coakley, “Kenosis: Theological Meanings and Gender Connotations,” in The Work of Love: Creation as Kenosis, ed. J C Polkinghorne (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2001), 200–202. Outlines overlap and differ in leading scholars’ descriptions of a “kenotic account of the creator’s relation to the creation.”

[50] Paul D. Molnar, “The Function of the Trinity in Moltmann’s Ecological Doctrine of Creation,” Theological Studies 51 (1990): 687.

[51] Daniel L. Migliore, “The Good Creation,” in Faith Seeking Understanding, 4th edn (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2023), 15.

[52] Webster, “Trinity and Creation,” 12.

[53] Hoggard-Creegan, “Vestiges of Trinity,” 204.

[54] Polkinghorne, Science and the Trinity, 75.

[55] Migliore, “The Good Creation,” 11.

[56] Migliore, “The Good Creation,”14.

[57] David Bentley Hart, The Beauty of the Infinite: The Aesthetics of Christian Truth (Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans, 2004), 254.

[58] Hoggard-Creegan, “Vestiges of Trinity,” 205.

[59] McGrath, A Fine-Tuned Universe, 164.

[60] Hoggard-Creegan, “Vestiges of Trinity,” 204.

[61] Polkinghorne, Science and the Trinity, 62.

[62] Lubitz et al., “Water Oxidation,” 109.

[63] Nancey C. Murphy and George F. R. Ellis, On the Moral Nature of the Universe: Theology, Cosmology, and Ethics (Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 1996), 213.

[64] Holmes Rolston, Genes, Genesis, and God: Values and Their Origins in Natural and Human History (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999), 307.

[65] Service, Triune Well-Being, 25.

[66] Robert Boyle, The Christian Virtuoso (1692–1744), in The Works of Robert Boyle, ed. M. Hunter and E. B. Davis, 14 vols. (New York: Routledge, 2016), 530.

[67] Harold Fisch, “The Scientist as Priest: A Note on Robert Boyle’s Natural Theology,” Isis 44, no. 3 (1953): 252–265, esp. 254 (citing Boyle, Of the Usefulness of Natural Philosophy, Part I), https://doi.org/10.1086/348227.

[68] David Bentley Hart, “Beauty, Being, Kenosis,” in Theological Territories: A David Bentley Hart Digest (Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 2020), 255.

[69] David Bentley Hart, The Experience of God: Being, Consciousness, Bliss (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2013), 35.

[70] Sergiĭ Bulgakov, The Lamb of God, trans. Boris Jakim (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2008), 126.

[71] Bulgakov, The Lamb of God, 127.

[72] Bulgakov, The Lamb of God, 121.

[73] Bonaventure, Breviloquium, Works of St. Bonaventure trans. Dominic Monti (New York: Franciscan Institute Publications, 2005), 96.