Abstract: Joseph Needham’s Science, Religion and Reality,[1] published in 1925, was an extraordinary contribution to the science and religion dialogue. Coming during the interwar physics revolution, it is a forgotten and underappreciated collection from Cambridge that helped trigger several important pieces that shaped the discussion at an academic and popular level. The collection brought together an accomplished group of religious scientists, predominantly connected with Cambridge University, that held different perspectives on how science and religion interacted but agreed on their ability to relate. However, for a variety of reasons, it has remained obscure despite its immense influence at the time. Here, I explore its content and the value it still has in the present day.

The dialogue concerning science and religion in interwar Britain was termed by the BBC in 1931 as “the great question of our time,”[2] but reaching this point was the crescendo of a complicated period. The late nineteenth century and early twentieth century saw strong, anti-religious popular publications meet religious revivals on both sides of the Atlantic, each of which considered religion and science to be opponents. The most historically notable examples were Andrew Dickson White’s A History of the Warfare of Science with Theology in Christendom (1896) and John William Draper’s History of the Conflict between Religion and Science (1874). Indeed, Lord Balfour makes explicit reference to this in his introduction to Science, Religion and Reality.[3] Professor Matthew Stanley notes that this was a very difficult time to be a religious scientist, as fundamentalism was often forcing one to choose a side.[4]

Following the First World War, physics and astronomy saw major upheaval through Einstein’s Relativity theory, which by the mid-1920s was being applied to the universe in what would eventually be formulated as the Big Bang Theory in Georges Lemaître’s 1927 paper, which Sir Arthur Eddington would see translated into English.

Both Oxford and Cambridge Universities featured many scientists that had religious faith. With the popular dialogue declining, and nuance being lost in public media, a more concerted effort was made to bring higher levels of dialogue to the public. The annual Gifford Lectures[5] were being published each year, having been established in 1887 by Adam Lord Gifford, in Scotland, to explore natural theology through the lectures of an eminent scholar. This built upon the nineteenth-century work of The Bridgewater Treatises and other published efforts in natural theology. However, these were not always scientific in nature, instead often featuring a voice from philosophy or theology. As publications such as The Freethinker (established in 1881 and then widely published from 1916) became more widespread, the conflict thesis was gaining momentum.

The largest public conflict came in 1925 with the Scopes Trial in Tennessee, where a schoolteacher, John Scopes, was found guilty of teaching human evolution to his students. The trial was broadcast globally, including by the BBC, and became a national representation of science pitted against religion in the courtroom. Given the large number of religious academics at Cambridge University, various outlets began to emerge for a more nuanced and elegant discussion of the interplay between science and religion from the academic to the public sphere, with expectation that this would sell strongly. Matthew Stanley describes the effort as follows:

In 1925 a volume appeared titled Science, Religion and Reality. Edited by Joseph Needham, it brought together an eclectic mix of philosophers, scientists, and historians to consider the relationships of religion and science from the perspectives of their disciplines. Needham sought to help round out human character by having “some feeling” for each of the forms of human experience, including religion and science.[6]

The editorial committee was chaired by the Reverend W. R. Inge (more commonly referred to as Dean Inge) and included seven Cambridge University officials, and one from Oxford University. The book itself was edited by Joseph Needham, fellow of Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge University.

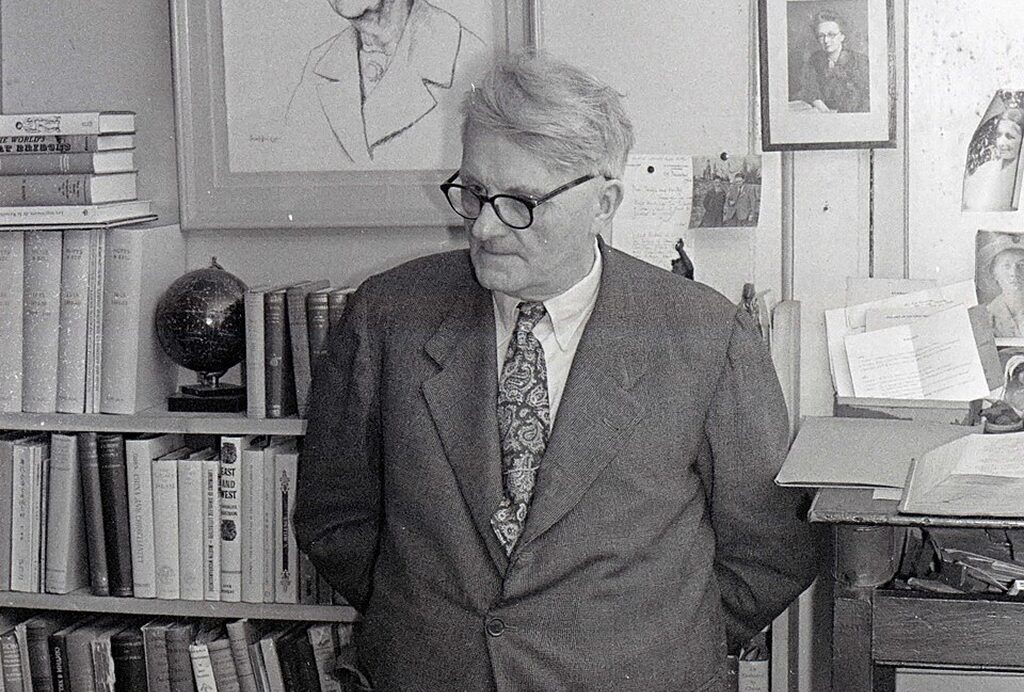

Needham was a prolific polymath, who was only 25 years old at the time of publication. He gained his bachelor’s degree, MA, and PhD from Caius College, all by 1925.[7] He was immediately elected a fellow of the college and later became a fellow of both the Royal Society and the British Academy. A young prodigy, he contributed several books to the dialogue around science and religion through the twentieth century. He later won the Leonardo da Vinci Medal in 1968 for his work on the history of science,[8] as he moved more from chemist to historian. Undoubtedly, the power of the collection came from the bigger names at the time, most notably Sir Arthur Eddington (1882–1944).

Significance

Eddington’s expositions of Relativity sold in huge numbers in the years preceding Science, Religion and Reality. He had not yet explored the religious implications for the theory, but following the release of Science, Religion and Reality this would change. As Stanley explains: “Relativity became a serious religious issue only in the late 1920s and 1930s, when practicing, cutting-edge scientists like Eddington, Jeans, J. D. Bernal, and Joseph Needham became major players in the debate about religion and science.”[9] Indeed, all mentioned would publish their own popular works extending the thoughts of Science, Religion and Reality. The collection became the trigger for a flurry of influential, thought-provoking books that sold in high numbers, as the appetite for the discussion of science and religion grew in its wake.

Eddington had become a huge name following his proof of Relativity in 1919, when he sailed to Principe Island off the coast of Africa with Frank Dyson. His photographic plates demonstrated the incredibly accurate predictions made of the deflection of starlight caused by the sun’s bending of spacetime due to its gravitation. He published three books between 1920 and 1923 on Relativity for the general public, making him the highest authority in the English language on the matter. As a result, Eddington sold well and had a large audience for whatever he said and became one of the premier science communicators of the 1920s and 1930s. For Needham to gain him as a writer for this collection guaranteed a strong audience in 1925, from a public still eager to understand the implications of this new theory for the world around them.

Content

Lord Arthur Balfour, former Prime Minister, Chancellor of Cambridge University and Fellow of the Royal Society, gave the introduction to the collection. The professorship in genetics at Cambridge has carried his name since 1912. Known for his philosophical reflections on evolution and genetics, it was undoubtedly significant to have him open the collection. Balfour castigates the late-nineteenth century predictions that science would replace religion, and the accompanying pessimism that still remained as to whether religion could survive the technological advancements underway. He points both to history and to the quality of contributors to the volume as strong evidence that scientific advancement could never overcome the place of religion. With that settled in his eyes, he moves on to the more relevant questions raised in the volume, as well as the issue of how the two interrelate. He queries what one is to do with miracles, or how someone should respond to new scientific data that confronts personal faith. These foreshadowed the answers given by the other contributors, but also the later works of writers such as C. S. Lewis.

Balfour gives reference to his own Gifford Lectures a decade earlier, which is an action repeated by other authors in a signpost intended to draw awareness to the far larger dialogue that was present in science and religion. The general public is heralded to note that despite incidents such as the Scopes Trial and the calls of growing humanism that science had outcompeted religion, the dialogue was grander than this.

The next contribution is by Dr Bronislaw Malinowski who was Reader in Social Anthropology at the University of London School of Economics. This interesting chapter seeks to understand the global trend of religion along with its universal superstitions. Malinowski, although not a Cambridge academic, was celebrated at the time for his exposition of religions’ ubiquity and historical dominance of humankind. Together with Eddington and Inge, he also contributed to the BBC’s first ever symposium on science and religion (September–December 1930, published in 1931).[10] We are unsure of the reasons behind the order of the chapters, but undoubtedly this was of great interest to a world of empires.

The following two chapters also addressed the historical nature of religion. Dr Charles Singer, Lecturer in the History of Medicine at the University of London, traces the history of humanity from its primitive beginnings to the modern day, carrying on the exploration of Malinowski. Whereas Malinowski places his emphasis on superstition and “magic,” Singer is more interested in how humans have landed in a secular frontier where the supposed battle lines had been drawn. In the following chapter, Dr Antonio Aliotta, Professor of Philosophy at the University of Naples (translated from Italian by Fred Brittain from Jesus College, Cambridge University) focuses on the nineteenth century alone. This is a fully philosophical evaluation of the various perspectives on the dialogue over science and religion, from Kant to Positivism. He concludes with a survey of the extensive landscape and critically examines modernism, giving particular focus on the value of pragmatism. “Positive religion” is the happier place, he argues, by insisting that “It is of no use to ask, for example, whether the dogmas of Christianity correspond to objective entities; its truth must be measured by its historic efficacy, and by the organisation of souls into a concrete harmony which it has been able to realise for so many centuries through the medium of its dogmatic and ritual structure.”[11]

At this point we have found that the goal of the book was to raise the conversation to a higher plane of dialogue, but in doing so the discussion is very much antagonistic to fundamentalism. Religion is discussed in its social and historical value, as being a more satisfying philosophical alternative to atheism, and as being interesting for its rich breadth and depth rather than being literally true in any regard.

The most celebrated chapter of the collection is given next by Sir Arthur Eddington, Plumian Professor of Astronomy at Cambridge University and Fellow of Trinity College. Stanley describes this first greater foray into religious writing by Eddington:

His contribution represented the culmination of his thinking on relativity by itself … and was his first explicit public statement on the relation of science and religion. However, despite the apparent introduction of religious elements into his philosophy, it was in no way a departure from the ideas he had been developing. Indeed, “The Domain of Physical Science” was a natural outgrowth and likely put forth ideas that he had held for some time.[12]

For context, at this time Eddington had made a habit of short philosophical reflections to end his various books on relativity and stellar physics. However, this is a solely philosophical and religious exposition. Given the new world that physics has brought, Eddington’s chapter “The Domain of Physical Science” sets out to sketch its implications for materialism. The physical universe and how we describe it are more constrained and narrower in scope than previously thought by the public, and those seeing the triumphs of the new physics as further development over religion are very mistaken:

The core of the essay was the establishment of the legitimate boundaries of the scientific conception, illustrated with the image of the simple act of stepping into a room. The common man unhesitatingly strides forward, but the physicist hesitates: the floor’s solidity is an illusion, and in truth it is an insubstantial web of hurtling atoms and shifting force fields. This parable does double duty for Eddington. First, it shows the dramatic divorce between the scientific and everyday conceptions of the world. Second, it shows the limitations of the use of the scientific conception. We must not insist on it constantly or we cannot function. Instead, expediency should be our guide on its application.[13]

Relativity had now vanquished the idea that science could explain everything. Physics is now more restricted, not less. His call extends not only to the public, but to his fellow physicists whose work was now reduced to pointer readings and measurements.[14] Eddington would greatly extend these sentiments in his later works The Nature of the Physical World, Science and the Unseen World, New Pathways in Science, and Philosophy of Physical Science. As Rupke explains, “A materialist view of the world demands a strong view of natural law and causality. Relativity shows that such laws are dependent on human intellect, and less on the world. Quantum theory allows one to disassemble the materialist view even further by undermining the possibility of precise human knowledge about the world.”[15]

Eddington does not propose that Relativity is evidence for God as such, rather it is evidence against a strict materialism.[16] This became one of the best expositions of what many more religiously minded scientists would explain through the interwar period, including Edward Arthur Milne and Sir James Jeans. Idealism would return with a vengeance from within the physics department at Cambridge University, despite the corresponding anger of Bertrand Russell and many of the Logical Positivists. However, though not direct evidence for God, Eddington would later (especially in Science and the Unseen World)[17] make clear “That the world took any coherent form was evidence for a world beyond the material: the spiritual.”[18]

Unsurprisingly, as a Quaker, he was fiercely opposed to dogmatism, and this extended in his scientific philosophy to materialism which he saw as too prevalent.[19] Nicholas Spencer has recently marked the release of Science, Religion and Reality as the moment Eddington made his full-fronted public attack on materialism and his campaign for his own brand of idealism.[20] His writing makes clear the importance of relativity for his mystical view of the world in how it aligns. Determinism had no ground left to stand on.[21] Eddington also used this work to further emphasise his repeated claim that the stuff of reality is mind over matter.

Although not proof-texting, Eddington is not shy in quoting the Bible. He capitalises “Mind” and “Logos” when making references to God[22] and does not generalise as much as the prior contributors. This is perhaps surprising given his Quaker faith over the more scripturally focused affiliations of the others.

Joseph Needham’s exploration of biology and consciousness well explains the considerations over a vital life force at the time. Notable geneticists such as Ronald Aylmer Fisher were publicly exploring what it was that vitalised living things from their chemical constituents. “Vitalism” would be dead by the birth of molecular biology after the Second World War, but at this point it was a serious topic of dialogue in religion and science from the life sciences.

Needham emphasised that explanations are needed at different levels.[23] Tiers of explanation exist of which the scientific, mechanical explanations serve as the lowest tier, giving a functional description of life. However, as one moves up tiers to the wholistic and then social descriptions, the functional scientific description becomes unsatisfactory. We can regard Needham’s chapter as of historical interest into the critiques of vitalism at the time, but the greater value comes in these views of analysis. Appeals to the soul, either from the realm of mind or from intuition or personality remain a point of emphasis.

Dr John Oman was Principal of Westminster College at Cambridge University. His chapter is concerned with linguistic analysis over the definition, role, and scope of religion and religious explanation of the world. Indeed, after Needham’s chapter, the analysis from scientists ends and moves into the humanities. Dr William Brown, Reader in Mental Philosophy from Oxford University explores psychology and mysticism in religion, before Dr Clement Webb of the philosophy faculty at Oxford University gives a shorter analysis of religion as a civilisation builder and what a scientific and Christian civilisation should be, considering the growth of secularism.

Dean Inge, who never seems to write in brief,[24] gives a lengthy conclusion. It is more his own reflections on the matter of science and religion, though he is in the privileged position of having read the other essays. Much of his well-read reflections on the finer points of religious reflection on science, from Bacon to DaVinci, are well worth reusing today as qualitative historical reflection. His writing is the most explicitly Christian of the book, though he is keen to note that his is not an apologetic defence of the faith.[25]

By this point, Dean Inge was well known for speaking in public, writing many (large) books and interjecting his voice into science and religion discussion. He himself gave a Gifford Lecture shortly before the end of the First World War. His conclusion was met with mixed reception, including this by Morgan in the Journal of Religion:

Dean Inge fulfils his reputation for wide learning and keen discernment, but he rarely leaves his readers in any danger of forgetting that he is above all things an orthodox theist and Christian mystic. Aside from the recognition of certain common problems, the makers of these essays display little unity in emphasis or technique. Despite the critical motivation of the volume, the aroma of apologeticism is somehow pervasive. The essays add strength to the conviction that man will long prove adept in finding reasons for his faith. It may be that science is destined to play a more minor role in the religious thinking of the future than we now suppose. It must be remembered that modern world-views inconsistent with historic Christianity certainly owe as much to anthropology, comparative religion, biblical criticism, and allied branches as to the contributions of the physical sciences. It becomes patent, therefore, that in the task of reconstructing religion for tomorrow, neither the scientist nor the theologian can be left unaided.[26]

The book by its end is large at 396 pages, rich in depth and breadth. It warranted, and received, an ample response.

Immediate Impact

As noted previously, the book first served to change the conversation away from extremes. Given its size and scope, it was a thorough response to the polemics that emerged from the end of the nineteenth century by Dickson White and Draper. The conversation would only grow in intensity as Bertrand Russell would publish Why I Am Not a Christian (1927), The Scientific Outlook (1931), and Religion and Science (1935) over the following decade. Eddington, among his aforementioned publications, wrote his own brief counter in Why I Believe in God: Science and Religion as a Scientist Sees It (1930).

Undoubtedly, the organisation of Cambridge academics to create this high-level discussion was impactful for a general public unsure of what the implications were for the new physics on religious belief. This is reflected in the extraordinary sales numbers for the books of Eddington and Jeans.

Different voices were platformed by Needham and the committee from London, Oxford, and Naples. The collective voice was more powerful than a single one and is harder to counter. Park noted the value of this symposium as follows:

Symposiums are interesting and instructive mainly because they reveal the wide divergences in point of view of the persons who contribute to them. One who expects this of symposiums in general will not be wholly disappointed in the present volume. After a careful reading of the distinguished contributors, one gets the notion not only that they are not all talking about the same things, but that they do not wholly understand one another. This too is more or less inevitable, since they are not all communicating in the same universe of discourse. Still it is interesting to know what men as different in temperament, training, and outlook on life as Arthur William Balfour, who writes the Introduction to the volume, and Dean William R. Inge, who writes the Conclusion, would say or could say about the same subject; it is interesting to know what such distinguished men would say on any subject. Aside from the contributions of these two men there are several papers in this collection which have individual and independent importance. This is particularly true of the paper by Antonio Aliotta, “Science and Religion in the Nineteenth Century,” and the paper “The Domain of Physical Science,” by Arthur S. Eddington.[27]

Writing for The Philosophical Review, Chambers celebrated the impact of the volume for countering a conflict narrative that had come to dominate popular circles in his review:

What, then, is the relation of science and religion? Not rival claimants for the realm of reality, but allies in the search of truth. For science maps out the structure of reality, while experience reveals its content. Whether, then, religion be a distinct variety of experience or the integral concord of all our experiences, it is not the enemy of science, except as science denies or ignores where it should observe and describe. From science to religion, from religion to science—that is the eternal rhythm of the process of the spirit, which rises from life to thought and returns from thought to life in a progressive enrichment which is the attainment of ever higher levels of reality and truth.[28]

Others were more balanced in their critique.[29] Morgan, writing for the Journal of Religion, noted the power of Eddington’s essay, but wondered why he diverged from other physicists in his Christian interpretation.[30] He was, however, more satisfied with Needham’s exposition of why vitalism and neovitalism were not viable and the warning of nailing religious colours to the mast of the latest speculations in biology.[31]

Most skepticism was reserved for the other authors, with Morgan keen to bring down any gathering excitement for the collection to be seen by believers as a new scaffolding upon which to construct proofs of God:

Oman attempts to construct a concept of the supernatural on the basis of values. His contentions are neither new nor overwhelmingly convincing. Brown … occupies himself with a distinction between individuality and personality and postulates God as the only complete person, “the totality of Reality itself.” Webb insists upon the leavening and directing influence of a Christian ethic, lest science become “but a powerful instrument in the hand of passions and interests,” and consequently a menace to future civilisation. The concluding essay by Dean Inge is characteristic. He has no sympathy with efforts to reconcile religion and science on the basis of a delimited territory. He asserts that the Copernican cosmology “tore into shreds the Christian map of the universe.” He insists that the Christian heaven can no longer be regarded as a place.[32]

Whilst the critical, academic response was predictably mixed, it accelerated the popular writing on the topic over the interwar years, with many more academics interjecting their voices into the science and religion dialogue.

Why It Has Remained Obscure

At this centenary retrospective, one wonders why this particular work has not received more historical acclaim. I offer three reasons in brief:

The Conversation Moved on as Individual Works Came to Dominate

Following its release, a far bigger platform was presented for individual published works to dominate the landscape of the science-religion dialogue. Eddington would release five works on the subject in the next decade, followed in competition by Sir James Jeans, and later Edward Arthur Milne. Inge would release his work God and the Astronomers, whilst the response would come from Bertrand Russell, Susan Stebbing,[33] and Chapman Cohen,[34] to meet the rise of religious scientists. Despite the BBC’s symposium, it was the rapid rise of individual popular works that would take the place of symposiums.

The BBC Symposium

As mentioned, the BBC’s first ever symposium on science and religion was a landmark program. Taking place in 1931, it gathered the growing momentum from works by Jeans and Eddington and extended the reach of the dialogue much further, which obscured the influence of Science, Religion and Reality. Accompanied by radio, the symposium was grander in scope and audience.

Eddington Memorial Lectureship and The Gifford Lectures

Following Eddington’s death in 1944, the annual memorial lectureship in Cambridge would join the Gifford Lectures in producing published reflections on the intersection of science, philosophy, and religion for much of the twentieth century. Cambridge University Press would publish these, bringing a steady supply of individual reflections on the subject. Both continue to this day, although the Eddington Lectures now focus only on astronomy. Once the printed annual lectures were successfully distributed, symposiums became less prominent.

Concluding Remarks

Undoubtedly, the Second World War added to the reasons for this seminal work being ignored to the extent that it has been. In considering this environment, and the tensions of interwar physics, the work demonstrates extraordinary timing and is an impressive collection.

Despite the representation from Oxford, London, and further afield, the work was a Cambridge phenomenon in its instigation and execution. Cambridge University had maintained a generous dialogue on science and religion for centuries and this work carried on the tradition of Newton and others in this regard.

The review in Nature upon its release sums up the success of it, as follows:

There has been of late a recrudescence of interest in the relations between science and religion, and the present book is a solid and important contribution to the study of this question, so fundamental for every thinking man. The book is remarkable also as showing how great a change has taken place in the attitude both of the theologian and of the scientific man towards this ever-present problem. The hearty days are gone when Huxley gave battle to the bishops, and fierce controversy raged through the pages of the serious reviews. In this book the spirit of antagonism is gone, and there is an earnest seeking after not compromise, but reconciliation. The pages breathe a sweet reasonableness, and one almost longs—in unregenerate moments—for a little clashing of swords.[35]

Despite this praise, the conflict was not gone, as is reflected in Russell and others bringing their counteroffensive in the writings that followed. But where Needham, Eddington, Balfour, and others succeeded is that these counteroffensives were not coming from the writing of scientists, but philosophers and popular writers. The growing public perception through the 1920s–1930s was that scientists were penning a different perspective on science and religion.

We must also reflect on Science, Religion and Reality as Needham’s work. Despite his youth, this was the first popular work of the young polymath and set the course for his own writings in both science and the science-religion dialogue. Most notably, he would follow up with his own extensive volume of lectures on the matter in The Great Amphibium.[36] Throughout his long life, Needham would give lectures on matters of faith that would be transcribed and printed for popular release. His most famous contributions to the history and philosophy of science came as he set out to explore the historical reasons as to why Chinese and Indian civilisations did not develop science and technology as the Western world did.[37]

As Stanley noted, Eddington’s chapter “The Domain of Physical Science,” published in Needham’s volume, was the first occasion that he extended his idealist philosophy and religious epistemology to the public, with reference to Relativity: “For Eddington, mind and consciousness were identical with spiritual values, and the recognition of the former was a recognition of the latter.”[38] And Eddington’s work in the volume made the most headway with the general public. No wonder that his The Nature of the Physical World, released in 1928, sold 90,000 copies.[39] He articulated in common, more accessible parlance, the moral and ethical framework in conjunction with scientific and broader philosophical ideas that the modern churchman could utilise. Because Eddington would go on to be the most popular expositor of religion and science for the interwar period (with Jeans), we cannot understate the importance of his first contribution, published in Science, Religion and Reality. It set the table for his later success. Eddington’s popular success in turn built the platform for future writings by Jeans, Milne, and others.

The author reports there are no competing interests to declare.

Received: 27/03/25 Accepted: 26/06/25 Published: 16/08/25

[1] Joseph Needham (ed.), Science, Religion and Reality (London: The Sheldon Press, 1926).

[2] Science and Religion: A Symposium (London: Gerald Howe Ltd, 1931).

[3] Needham, Science, Religion and Reality, 3.

[4] Matthew Stanley, Practical Mystic: Religion, Science, and A. S. Eddington (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007), 194, 235.

[5] See https://giffordlectures.org/

[6] Stanley, Practical Mystic, 184.

[7] Maurice Goldsmith, Joseph Needham: 20th Century Renaissance Man (Paris: UNESCO Publishing, 1995), 31.

[8] https://www.historyoftechnology.org/about-us/awards-prizes-and-grants/the-leonardo-da-vinci-medal/

[9] Stanley, Practical Mystic, 192.

[10] Science and Religion: A Symposium (London: Gerald Howe Ltd, 1931).

[11] Antonio Aliotta, “Science and Religion in the Nineteenth Century,” in Science, Religion and Reality, 186.

[12] Stanley, Practical Mystic, 184.

[13] Stanley, Practical Mystic, 184.

[14] Stanley, Practical Mystic, 185.

[15] Nicolaas A. Rupke (ed.), Eminent Lives in Twentieth Century Science and Religion, 2nd edn (Frankfurt: Peter Lang, 2009), 140.

[16] Stanley, Practical Mystic, 188.

[17] Eddington, Science and the Unseen World (London: Quaker Books, 2007).

[18] Stanley, Practical Mystic, 186.

[19] Rupke, Eminent Lives, 151.

[20] Nick Spencer, Magisteria: The Entangled Histories of Science & Religion (London: Oneworld Publications, 2024), 343.

[21] Jitse M. Van der Meer, Facets of Faith and Science, vol. 1: Historiography and Modes of Interaction (Lanham, MD: University Press of America Inc., 1996), 40.

[22] Eddington, “The Domain of Physical Science,” 217.

[23] See Niels Henrik Gregersen, “Emergence and Complexity,” in The Oxford Handbook of Religion and Science, ed. Philip Clayton and Zachary Simpson (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006), 771.

[24] See for example, W. R. Inge, God and the Astronomers (London: Longmans, Green and Co., 1933) for his own later work on Eddington, Jeans, and Milne, in particular.

[25] William Ralf Inge, “Conclusion,” 347.

[26] W. J. Morgan, Review of “Science, Religion and Reality” by Joseph Needham, The Journal of Religion 6:5 (1926): 533–536, esp. 536, https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/10.1086/480610.

[27] Robert E. Park, Review of Science, Religion, and Reality, in American Journal of Sociology 32:1 (1926): 135–136, esp. 135, https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/10.1086/214040.

[28] L. P. Chambers, The Philosophical Review 37:1 (1928): 78–82, esp. 82, https://doi.org/10.2307/2179527.

[29] Another example is L. Arnauld Reid’s review in Hibbert Journal 24 (1925): 594. See also A. E. Elder’s review in Philosophy 1:1 (1926): 105–108, DOI: 10.1017/S0031819100014819.

[30] Morgan, Review of Science, Religion and Reality, 534.

[31] Morgan, Review of Science, Religion and Reality, 535.

[32] Morgan, Review of Science, Religion and Reality, 535.

[33] L. Susan Stebbing, Philosophy and the Physicists (London: Penguin Books, 1937).

[34] Chapman Cohen, God and the Universe: Eddington, Jeans, Huxley and Einstein (London: Pioneer Press, 1931).

[35] E. S. R., “Science, Religion and Reality,” Nature 117:2944 (1926), 475–478, https://doi.org/10.1038/117475b0.

[36] Joseph Needham, The Great Amphibium (London: Student Christian Movement Press, 1931).

[37] Clayton and Simpson, The Oxford Handbook, 30, 300.

[38] Stanley, Practical Mystic, 187.

[39] Rupke, Eminent Lives, 137.